NGTS-EB-8: An eclipsing binary discovered by you! (Part 1)

In my previous post describing the planet candidates that you helped discover as part of the Planet Hunters NGTS project, I mentioned the candidate TIC-165227846, an exciting system that at the time we believed to be a giant planet orbiting a small star. These kinds of systems are really interesting because they’re so puzzling. Planets form from material that orbits a new star in a disk-like structure called a protoplanetary disk. The amount of material in the disk correlates with the mass of the host star, so a really small star will have less material available for planet-building and therefore giant planets just shouldn’t be able to form! Given how interesting and rare this target was (at the time we found our candidate, there were only ~10 planets like this, and even now scientists have only found ~30 planets of similar size orbiting close to really small stars), we decided to get more observations to try and determine what kind of star-planet combination we were really seeing.

We’d already acquired speckle imaging observations (you can read more about what those are here) which told us that there probably wasn’t a nearby star that would give us a false impression of the transit depth. The next step was to get radial velocity observations. This technique works by detecting how much a star is “wobbling.” When we say the planets orbit the Sun, really we mean the planets AND the Sun orbit the entire Solar System’s common centre of mass, it just happens to be that this point is very close to the Sun since it’s so big. It’s the same story for exoplanets and stars orbiting one another, they all move around the system’s centre of mass. The wobbling that we detect from the host star is caused by any exoplanets or other stars that are orbiting it, and the amount of wobble relates to how much mass the object orbiting the host has. What this means is that if the star isn’t wobbling much, then it’s likely that the thing causing it to wobble is a planet, but if we see really large changes in the velocity of the star, or are even able to measure two different stellar signals, then we can determine that we are in fact seeing a binary star system, i.e. two stars orbiting one another!

We can measure how much the star is moving using spectrographs, which are instruments that split the light from stars into its individual wavelengths, similar to how a prism splits light into a rainbow. This allows us to see specific lines in the spectrum of the star that move depending on the relative velocity of the star due to the Doppler effect (the Doppler effect is the same effect that changes the pitch of an ambulance siren as it moves towards and away from you, it’s all about wavelengths changing with velocity).

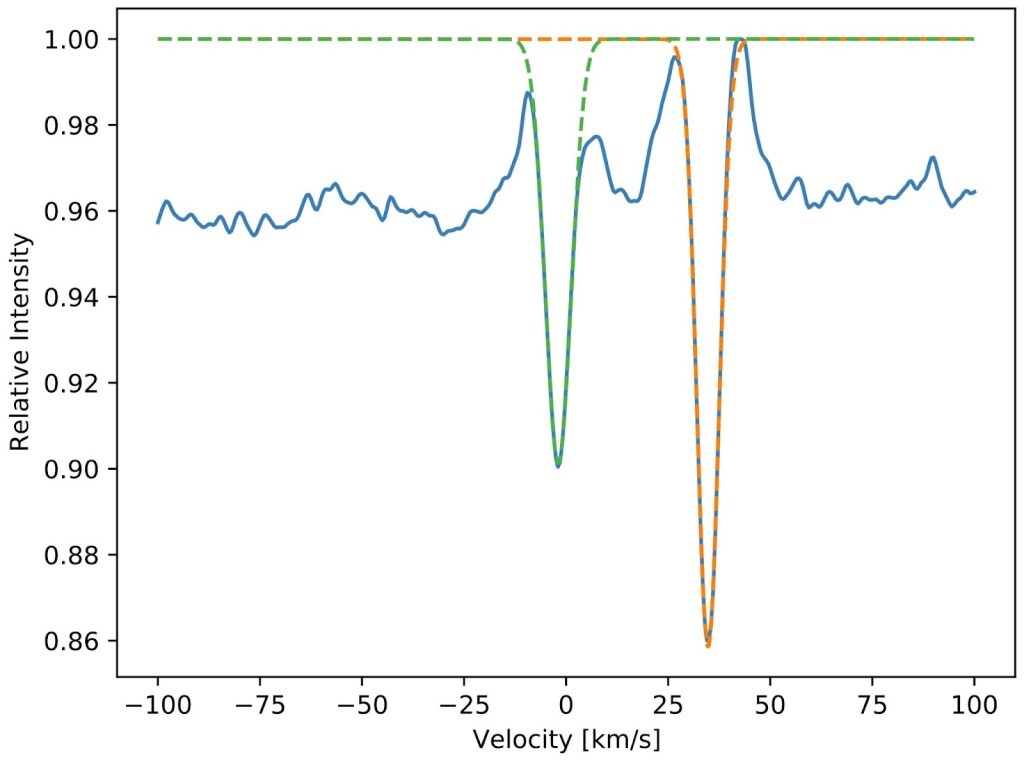

We first used the Near Infra Red Planet Searcher (NIRPS) instrument that is mounted on the 3.6-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. We took 9 different measurements of the system over the course of a month however because the system is so faint, we couldn’t definitively tell if we had detected a planet or another star orbiting really close to the host. We next obtained observations with the Gemini High-resolution Optical SpecTrograph, or GHOST (astronomers love their terrible forced acronyms), which is mounted on the 8.1-metre Gemini-South telescope in Cerro Pachon, Chile. The bigger telescope means that we could collect more light from the star and therefore overcome the issue of it being so faint. This allowed us to get good enough observations to get a more definitive answer. The image below shows the key information for diagnosing whether this system is made up of a star and planet or two stars. It’s called a cross-correlation function and this is the tool we use to measure those velocity shifts, with any large dips being caused by a star moving with the velocity that the dip matches up with on the x-axis.

And there it is! Two big dips in the intensity indicating that we in fact are looking at two stars orbiting one another! In Part 2 I’ll talk more about what we learned about this system and why we didn’t spot it sooner!

Trackbacks / Pingbacks