NGTS-EB-8: An eclipsing binary discovered by you! (Part 2)

In Part 1, I described the new observations we acquired for one of our candidates to try to determine whether it was an exoplanet, or, in fact, a binary star system. The crucial radial velocity measurements revealed the latter was true and in this post I will describe what we have since learned about the system as we analyzed it further.

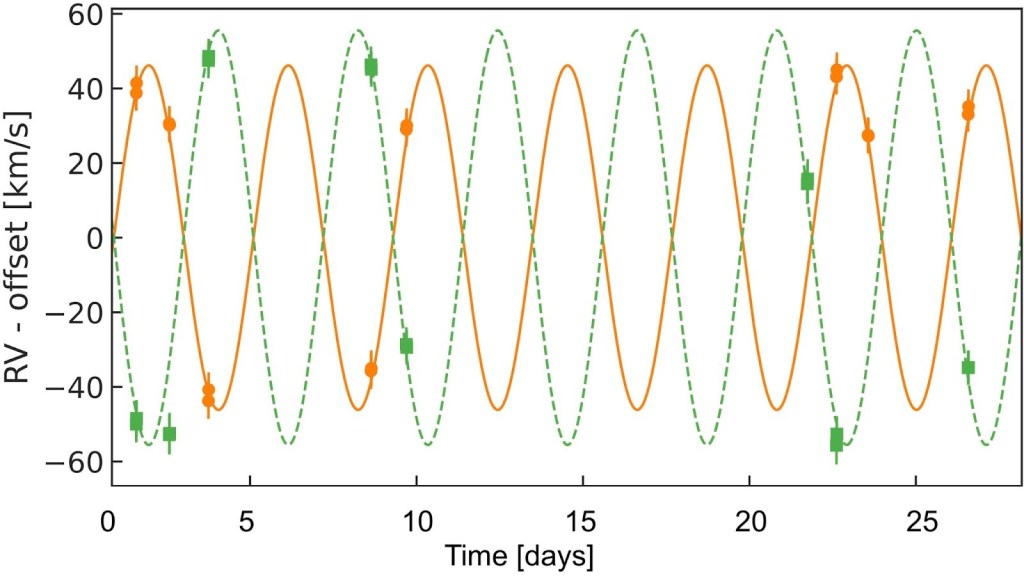

We took another look at the NIRPS observations with the knowledge that we were actually looking for two stars, and we were able to measure the radial velocities (RVs) across the whole month of observations for both stars. The image below shows these RVs in two different colors with the orange circles showing the velocity measurements for the larger of the two stars (the primary star) and the green squares showing the measurements for the smaller star (the secondary star). The lines show the best fit models to the data and these nice clear RV curves allow us to get a really good idea of the ratio of the masses of the two stars. The ratio of the masses is equal to 0.83, meaning the two stars are quite similar in mass (if they were equal they would have a mass ratio of 1, while a value closer to 0 would suggest they have very different masses).

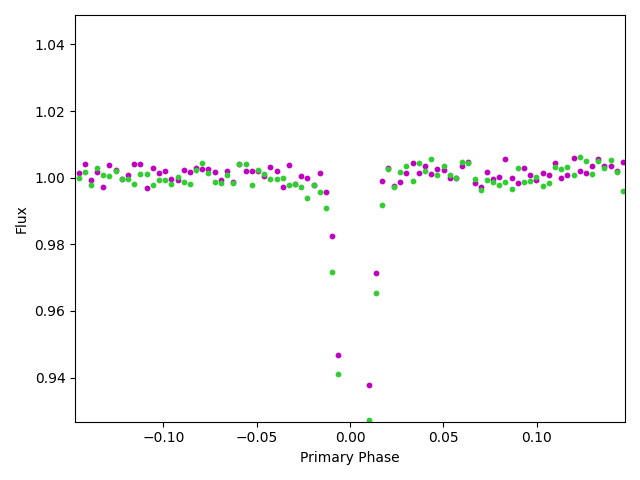

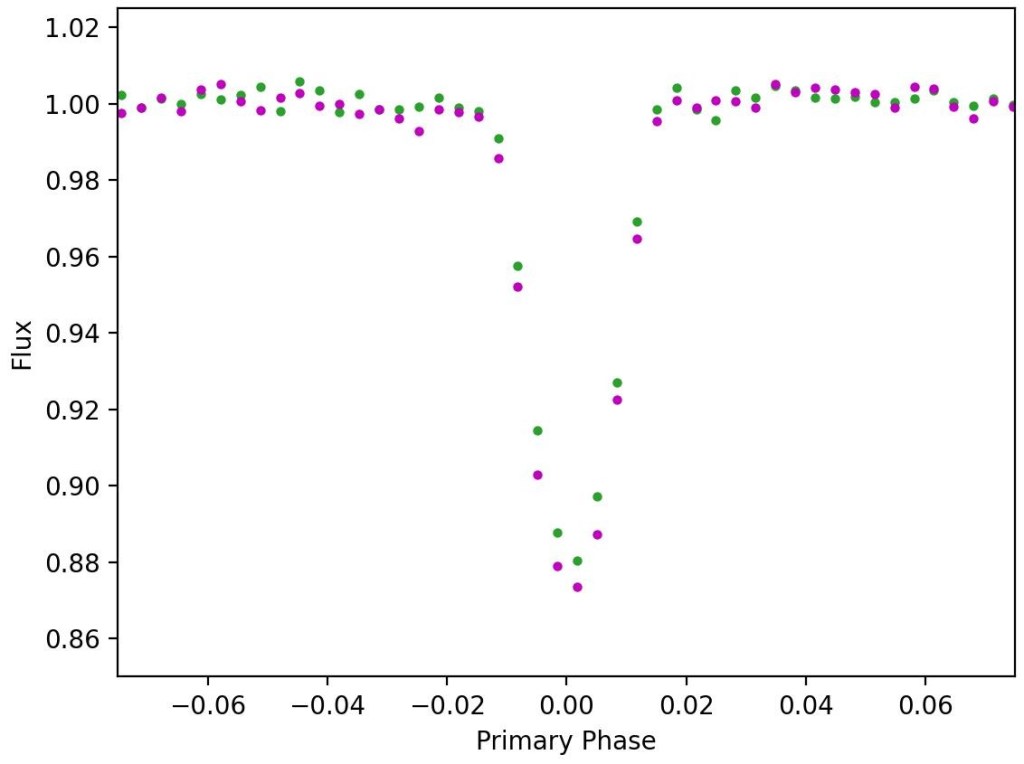

We were also able to determine that the orbital period (how often the stars go round each other) was actually double what we thought, meaning that they were orbiting one another every 4.2 days. This was an important discovery as this told us that what we had believed to be one object causing a transit every 2.1 days was actually two different eclipses! This is exactly the kind of thing the Odd/Even Transit Check is meant to spot, so why didn’t we? The plot on the left below shows the image that was classified in Planet Hunters NGTS and unfortunately the bottom of the transit was cut-off! This was because the algorithm that initially detects the transit signals underestimated the depth so then when the diagnostic plot was created it didn’t show the full extent of the transit. The plot on the right shows the odd/even for the full depth of the transit, which we were able to use to take a closer look at the data, and even here the difference between the depths of the green and magenta points is so subtle that it wasn’t enough to conclusively determine that this was in fact an eclipsing binary.

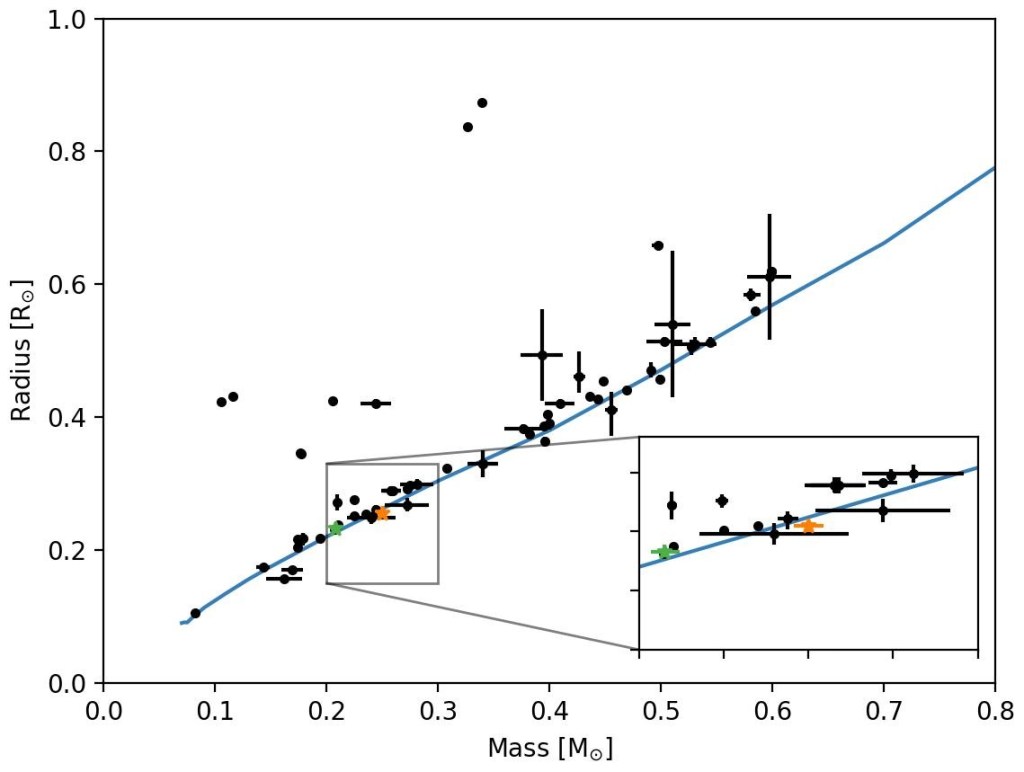

Equipped with our new knowledge of the correct orbital period, we were then able to model all the available data and derive measurements of the individual masses and radii of the two stars in the system. These are crucial measurements, as the mass and radius of a star allow us to compare it with other similar systems that have been discovered in the past and draw conclusions about whether the system follows theoretical predictions or deviates from what we expect! The image below shows different stars discovered in eclipsing binaries as black points and the theoretical mass-radius relation as a blue line (this is what theoretical modelling suggests should be the mass and radii of stars). The values on the axes are expressed in terms of solar units, meaning that our stars are approximately one quarter the radius of the Sun (~0.25 R⊙). The orange point shows the position of the primary star while the green point shows the position of the secondary star.

This plot shows us that both stars align well with the theoretical prediction (the blue line). That may sound obvious, but low-mass stars are a particularly interesting case where there is currently a “radius inflation problem” seen. The radii of low-mass stars that we discover in general appear larger than the theoretical models suggest (you can see how a lot of the black points sit slightly above the blue line in the plot), and so there is currently some confusion over the mechanisms that might be causing this. Therefore by discovering more systems that are aligned with the theoretical models, we can place better constraints on how significant this problem is, whether the models need to be altered, or if better observations could reveal more about the true masses and radii of all these stars. Eclipsing binary systems like this are generally really useful tools for calibrating other methods of estimating stellar masses and radii. As you can see, it takes a lot of observations and a lot of analysis to measure the masses and radii of just two stars. Therefore it’d be extremely impractical to have to do this for every single star we normally observe in a survey like NGTS or TESS and so we need different ways to determine the properties of most stars. By getting these accurate measurements that are independent of the typical methods used to determine stellar properties, we can calibrate the methods used to get even more accurate estimates of the masses and radii of a much wider range of stars!

While this system isn’t a planet orbiting a star as we had initially thought, it’s still a really interesting and valuable system that will hopefully be useful to astronomers in the future. This discovery wouldn’t have been possible without the Planet Hunters NGTS project and to recognise the important role that citizen scientists played in this discovery, the names of all those who classified this system in Planet Hunters NGTS (and gave consent for their name to be used) are included in the author list of the journal article! The official journal article will be available at the following link in a few weeks: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ae0e0d, but you can already read the pre-print version on arXiv here: “NGTS-EB-8: A Double-lined Eclipsing M+M Binary Discovered by Citizen Scientists”.