NGTS-EB-8: An eclipsing binary discovered by you! (Part 2)

In Part 1, I described the new observations we acquired for one of our candidates to try to determine whether it was an exoplanet, or, in fact, a binary star system. The crucial radial velocity measurements revealed the latter was true and in this post I will describe what we have since learned about the system as we analyzed it further.

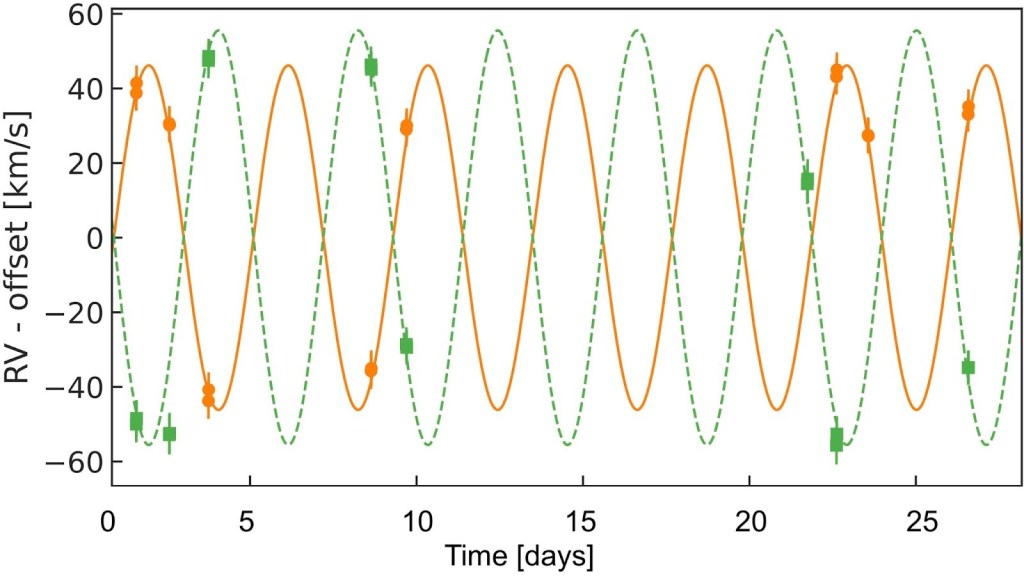

We took another look at the NIRPS observations with the knowledge that we were actually looking for two stars, and we were able to measure the radial velocities (RVs) across the whole month of observations for both stars. The image below shows these RVs in two different colors with the orange circles showing the velocity measurements for the larger of the two stars (the primary star) and the green squares showing the measurements for the smaller star (the secondary star). The lines show the best fit models to the data and these nice clear RV curves allow us to get a really good idea of the ratio of the masses of the two stars. The ratio of the masses is equal to 0.83, meaning the two stars are quite similar in mass (if they were equal they would have a mass ratio of 1, while a value closer to 0 would suggest they have very different masses).

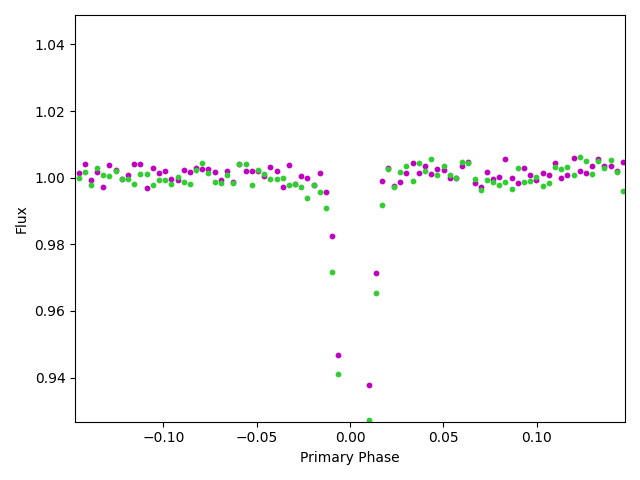

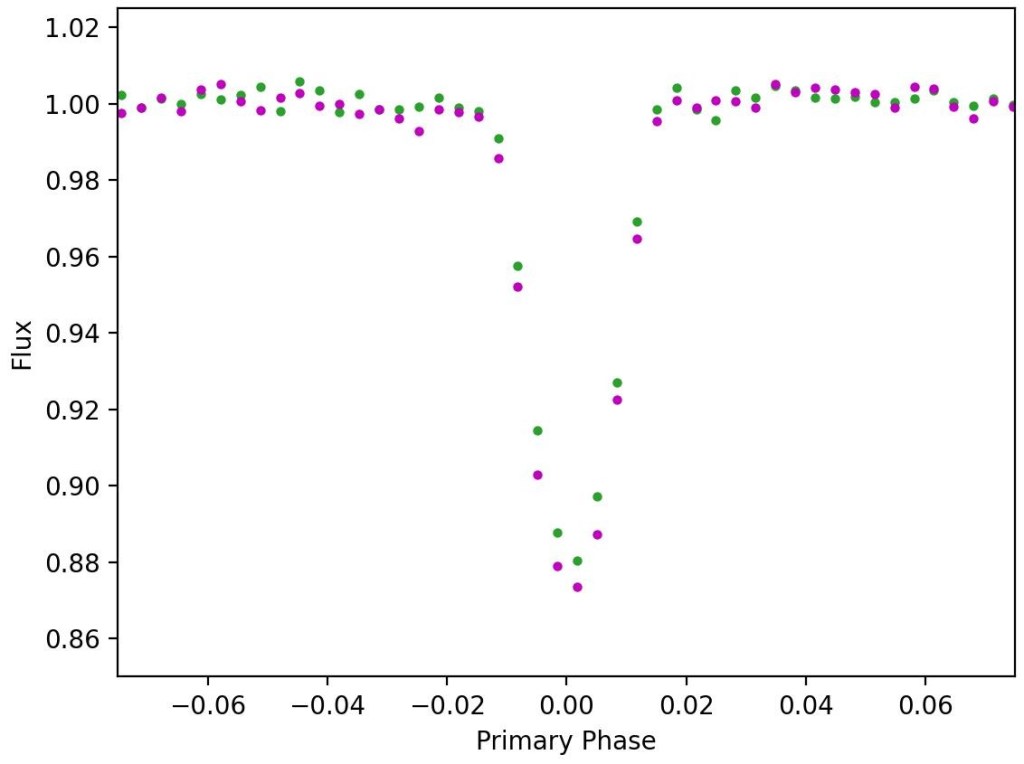

We were also able to determine that the orbital period (how often the stars go round each other) was actually double what we thought, meaning that they were orbiting one another every 4.2 days. This was an important discovery as this told us that what we had believed to be one object causing a transit every 2.1 days was actually two different eclipses! This is exactly the kind of thing the Odd/Even Transit Check is meant to spot, so why didn’t we? The plot on the left below shows the image that was classified in Planet Hunters NGTS and unfortunately the bottom of the transit was cut-off! This was because the algorithm that initially detects the transit signals underestimated the depth so then when the diagnostic plot was created it didn’t show the full extent of the transit. The plot on the right shows the odd/even for the full depth of the transit, which we were able to use to take a closer look at the data, and even here the difference between the depths of the green and magenta points is so subtle that it wasn’t enough to conclusively determine that this was in fact an eclipsing binary.

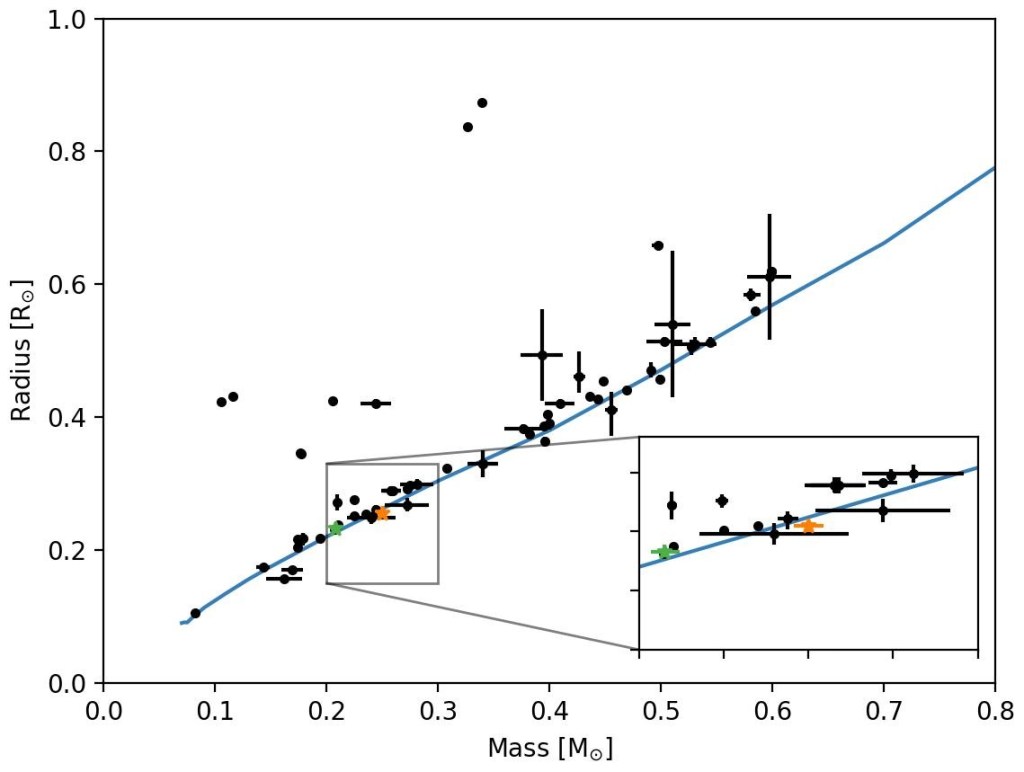

Equipped with our new knowledge of the correct orbital period, we were then able to model all the available data and derive measurements of the individual masses and radii of the two stars in the system. These are crucial measurements, as the mass and radius of a star allow us to compare it with other similar systems that have been discovered in the past and draw conclusions about whether the system follows theoretical predictions or deviates from what we expect! The image below shows different stars discovered in eclipsing binaries as black points and the theoretical mass-radius relation as a blue line (this is what theoretical modelling suggests should be the mass and radii of stars). The values on the axes are expressed in terms of solar units, meaning that our stars are approximately one quarter the radius of the Sun (~0.25 R⊙). The orange point shows the position of the primary star while the green point shows the position of the secondary star.

This plot shows us that both stars align well with the theoretical prediction (the blue line). That may sound obvious, but low-mass stars are a particularly interesting case where there is currently a “radius inflation problem” seen. The radii of low-mass stars that we discover in general appear larger than the theoretical models suggest (you can see how a lot of the black points sit slightly above the blue line in the plot), and so there is currently some confusion over the mechanisms that might be causing this. Therefore by discovering more systems that are aligned with the theoretical models, we can place better constraints on how significant this problem is, whether the models need to be altered, or if better observations could reveal more about the true masses and radii of all these stars. Eclipsing binary systems like this are generally really useful tools for calibrating other methods of estimating stellar masses and radii. As you can see, it takes a lot of observations and a lot of analysis to measure the masses and radii of just two stars. Therefore it’d be extremely impractical to have to do this for every single star we normally observe in a survey like NGTS or TESS and so we need different ways to determine the properties of most stars. By getting these accurate measurements that are independent of the typical methods used to determine stellar properties, we can calibrate the methods used to get even more accurate estimates of the masses and radii of a much wider range of stars!

While this system isn’t a planet orbiting a star as we had initially thought, it’s still a really interesting and valuable system that will hopefully be useful to astronomers in the future. This discovery wouldn’t have been possible without the Planet Hunters NGTS project and to recognise the important role that citizen scientists played in this discovery, the names of all those who classified this system in Planet Hunters NGTS (and gave consent for their name to be used) are included in the author list of the journal article! The official journal article will be available at the following link in a few weeks: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ae0e0d, but you can already read the pre-print version on arXiv here: “NGTS-EB-8: A Double-lined Eclipsing M+M Binary Discovered by Citizen Scientists”.

NGTS-EB-8: An eclipsing binary discovered by you! (Part 1)

In my previous post describing the planet candidates that you helped discover as part of the Planet Hunters NGTS project, I mentioned the candidate TIC-165227846, an exciting system that at the time we believed to be a giant planet orbiting a small star. These kinds of systems are really interesting because they’re so puzzling. Planets form from material that orbits a new star in a disk-like structure called a protoplanetary disk. The amount of material in the disk correlates with the mass of the host star, so a really small star will have less material available for planet-building and therefore giant planets just shouldn’t be able to form! Given how interesting and rare this target was (at the time we found our candidate, there were only ~10 planets like this, and even now scientists have only found ~30 planets of similar size orbiting close to really small stars), we decided to get more observations to try and determine what kind of star-planet combination we were really seeing.

We’d already acquired speckle imaging observations (you can read more about what those are here) which told us that there probably wasn’t a nearby star that would give us a false impression of the transit depth. The next step was to get radial velocity observations. This technique works by detecting how much a star is “wobbling.” When we say the planets orbit the Sun, really we mean the planets AND the Sun orbit the entire Solar System’s common centre of mass, it just happens to be that this point is very close to the Sun since it’s so big. It’s the same story for exoplanets and stars orbiting one another, they all move around the system’s centre of mass. The wobbling that we detect from the host star is caused by any exoplanets or other stars that are orbiting it, and the amount of wobble relates to how much mass the object orbiting the host has. What this means is that if the star isn’t wobbling much, then it’s likely that the thing causing it to wobble is a planet, but if we see really large changes in the velocity of the star, or are even able to measure two different stellar signals, then we can determine that we are in fact seeing a binary star system, i.e. two stars orbiting one another!

We can measure how much the star is moving using spectrographs, which are instruments that split the light from stars into its individual wavelengths, similar to how a prism splits light into a rainbow. This allows us to see specific lines in the spectrum of the star that move depending on the relative velocity of the star due to the Doppler effect (the Doppler effect is the same effect that changes the pitch of an ambulance siren as it moves towards and away from you, it’s all about wavelengths changing with velocity).

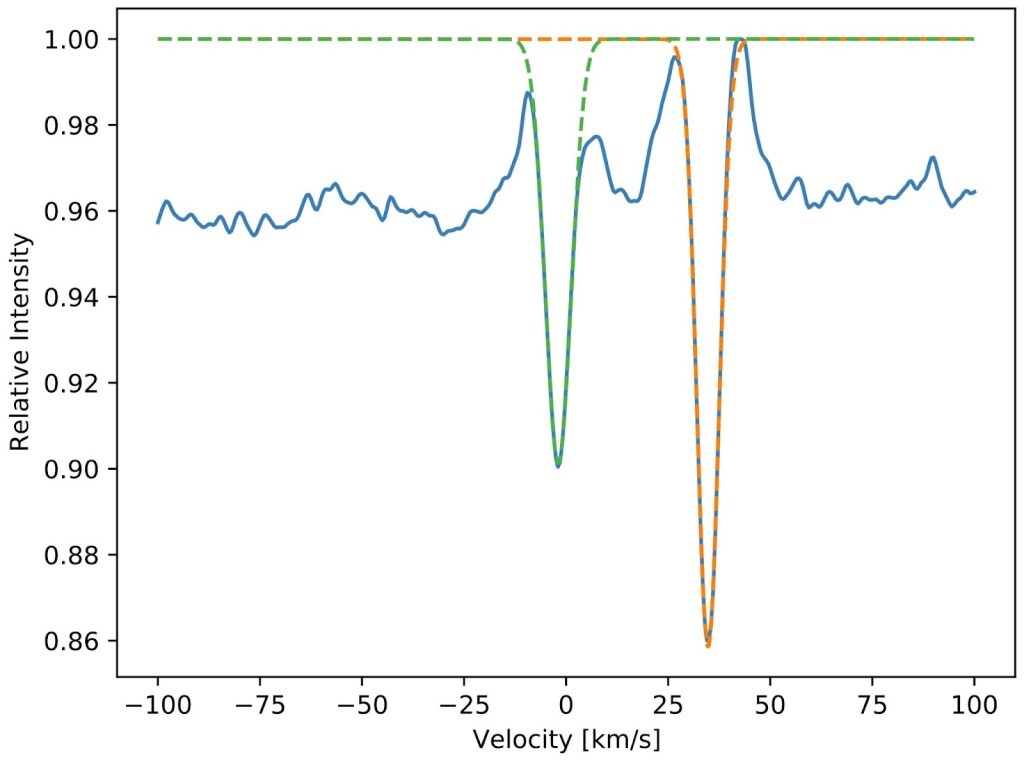

We first used the Near Infra Red Planet Searcher (NIRPS) instrument that is mounted on the 3.6-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. We took 9 different measurements of the system over the course of a month however because the system is so faint, we couldn’t definitively tell if we had detected a planet or another star orbiting really close to the host. We next obtained observations with the Gemini High-resolution Optical SpecTrograph, or GHOST (astronomers love their terrible forced acronyms), which is mounted on the 8.1-metre Gemini-South telescope in Cerro Pachon, Chile. The bigger telescope means that we could collect more light from the star and therefore overcome the issue of it being so faint. This allowed us to get good enough observations to get a more definitive answer. The image below shows the key information for diagnosing whether this system is made up of a star and planet or two stars. It’s called a cross-correlation function and this is the tool we use to measure those velocity shifts, with any large dips being caused by a star moving with the velocity that the dip matches up with on the x-axis.

And there it is! Two big dips in the intensity indicating that we in fact are looking at two stars orbiting one another! In Part 2 I’ll talk more about what we learned about this system and why we didn’t spot it sooner!

Published Planet Candidates from Planet Hunters NGTS!

Good news everyone! Our paper describing the Planet Hunters NGTS project and presenting the first 5 planet candidates discovered by the project has been published in the Astronomical Journal!

The paper goes into the nitty gritty details of how the project operates, how we combine all the responses we received for the first dataset we uploaded (over 2.6 million individual classifications!) and how the list of planet candidates are selected for further observations. The most exciting part of the paper is the section where we present the 5 new planet candidates found by you, the citizen scientists! These planet candidates were not previously identified by the NGTS team or as TESS Objects of Interest, meaning some of you were the first people to ever suspect these could be possible planets. The paper includes a link to the project results page which lists the names of all the citizen scientists who classified these candidates at any stage of the project and you can find that list here too! Although none of these candidates are “confirmed planets” yet, we’re continuing to gather and analyse more data on each of them and hope to announce the confirmation of one or more of these planet candidates in the near future. Even at this stage, these candidates are interesting discoveries, in particular the excitingly named TIC-165227846 and TIC-135251751, which I’ll give a bit more detail on below.

TIC-165227846 is an exciting system as it’s a rare find. We think this could be a giant planet (bigger than Jupiter) orbiting very close to a low-mass star known as an M-dwarf. There’s only around 10 of these systems that have been detected so far and, if confirmed, ours would be the lowest mass star to host a close-in giant planet discovered to date! These types of systems are interesting because, quite simply, we don’t think they should be able to exist. A newly formed star can be surrounded by what we call a “protoplanetary disk,” which is a load of dust and gas that provides the material necessary to form planets. We currently believe that most planets form via “core accretion” where this dust and gas sticks together and forms a planet over time. However the amount of material available in the protoplanetary disk correlates with the mass of the star, therefore a low-mass star such as this will have less material available to form such a large planet! Another barrier is the time it takes for a planet to form around a low-mass star is longer (the lower mass means that things move more slowly around it) but planet formation is on a time limit as the protoplanetary disk gets dispersed as the star evolves. By discovering interesting systems such as TIC-165227846 that challenge our current theories of planet formation, we can test and tweak our models to gain a better understanding of how planets come to exist.

TIC-135251751 is an interesting system with an even more interesting story of how we came to learn (part of) its true nature. When we first discovered this system, we thought we were seeing a giant planet orbiting close to an ageing star, known as a subgiant. Don’t be fooled by the name though as this star apparently had a radius 2.4 times that of our Sun. These kinds of systems are interesting because we don’t often expect to find planets close to stars that are evolving into the later stages of their lifecycle. This is because these stars begin to expand and can engulf any planets close to them. However, one of the key steps in validating whether or not a possible transit signal is really due to a planet is to obtain speckle imaging, which you can read more about here. In short, speckle imaging allows us to observe close to the host star to see if there are any other stars nearby that could be affecting our measurements. When we observed TIC-135251751 using the Zorro instrument at Gemini South, the wonderful Zorro team found that this star was actually two stars in a binary system! Though it doesn’t look like much, the slightly elongated shape of the red spot in the inset of the figure below is the evidence that tells us that this system is not as it initially seemed.

While initially disheartening to find that we were actually looking at two stars, meaning that further observations and analysis would be challenging, the reality is that the transiting signal we detect is possibly still due to a planet and is not a result of the 2 stars passing in front of each other (like an eclipsing binary). These stars are orbiting with a period of ~50 years while the transit signal occurs approximately every 4 days. We could be observing a planet orbiting one of the two stars in this close binary system which would be another interesting discovery for Planet Hunters NGTS as these types of systems also pose interesting questions for our theories on planet formation.

This paper and these discoveries are just the first step for Planet Hunters NGTS. We will continue to analyse these systems with the belief that we can report the confirmation of a bonafide planet soon. Meanwhile, we’ll continue to analyse the newer datasets as classifications roll in, including the latest data from NGTS which is live on the site now and hasn’t been looked at by anyone before. This means that you could be the first person to spot a new planet in the NGTS data, so get classifying and maybe one day we’ll be publishing a paper with a discovery you helped find!

A week in the life of an observer

Last month I had the privilege of observing at the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo (TNG) at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma. It’s convenient that often the conditions required for excellent observations are the same as what you’d look for in a warm holiday destination, although when you’re working night shifts there isn’t much time for sunbathing. Located at an altitude of 2,370 metres on the edge of La Caldera de Taburiente, the TNG is home to five instruments: SiFAP2, Nics, Dolores, GIANO-B and HARPS-N. We primarily used the HARPS-N instrument, or to give it its full name: the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher for the North hemisphere, because astronomers love an acronym. This instrument is designed to measure the radial velocity signal of stars. This is a technique that essentially detects how much a star is “wobbling,” from which we can determine the minimum mass of any orbiting body (if it’s low enough, then we have a planet!).

With no direct flights between Belfast and La Palma, we had to make a brief stopover in Tenerife before arriving in La Palma the following morning. A quick taxi ride up the mountain road and we reached the Residencia which would be our home for the next 9 days. Our observing run didn’t start until the next night which meant we had plenty of time to watch the sunset. The images below show the three other terrestrial planets in our Solar System with Venus shining bright near the horizon, Mercury (a rare sighting!) a short distance up and right of Venus, and Mars a bit further away up and to the left. Since my phone camera isn’t quite as good as a 3.58-metre, world-class telescope, I’ve annotated the image so you can be sure that those aren’t just smudges on your screen.

The typical “day” when on an observing run (in Summer, when the nights are short!) is as follows: Wake up around 3:30pm, grab a quick breakfast and head up to the telescope at 5pm to start calibrations and schedule the target list. Depending how quick we get calibrations done, we have some time to kill before eating dinner as late as possible then heading back up to the telescope for sunset (which for us is around 9pm). After watching the Sun dip below the horizon, we head into the telescope control room to review the schedule for the night, check the weather forecast to make sure there aren’t any pesky clouds inbound and, if needed, look for backup targets that can be observed in poor weather. We start scientific observations at the end of nautical twilight, which is when the horizon is no longer visible (so-called as this is the period when sailors could navigate using bright guide stars while still having sight of the horizon). Assuming the weather is clear and the telescope doesn’t have any technical faults, observing a set list of targets is quite straightforward and we continue to observe until the end of nautical night which is around 6:30am. After filling out the night report detailing what we observed and any issues that may have occurred, we head back down to the Residencia and get to bed around 7am to get as much sleep as possible before starting the same routine all over again.

Our first three nights of observing went pretty smoothly, with remarkably good conditions on night two. The seeing (a measure of how good your image quality is due to turbulence in the atmosphere) reached 0.19 arcseconds! I’ve provided a cartoon below to put into context how good the conditions were:

We passed some of the time getting other work done (as best we could when adjusting to a night shift) but mostly we played card games while checking that the observations were still on track. During our free time in the day, we took the opportunity to go up to the summit of the Roque de los Muchachos, which provides stunning views into the caldera (the remnants of a huge volcano crater) and across the island of La Palma. In the distance we could see the site of the 2021 Cumbre Vieja volcanic eruption which is still smoking to this day.

The fourth night of our observing run marked the midway point, and the weather had taken a comparative turn for the worse with high-level cloud rolling in throughout the night, disrupting our observations and leaving us to chase targets that were in any gaps we could spot. These conditions are more typical of an observing run, with variable conditions and time lost waiting for clouds to pass, so it was a useful experience to learn how to react when the weather won’t play nice.

The forecast for night 5 looked as though it could go the same way as the previous night, but luckily the clouds kept dissipating before they reached us. The final two nights of the observing run also went smoothly which gives me the opportunity to talk a bit about the interesting history of the TNG’s design. The TNG’s design is derived from that of the New Technology Telescope (NTT) which is located at La Silla Observatory in Chile. As the name suggests, the NTT pioneered many of the technologies which are widespread on many of the best telescopes today. It implemented active optics, where the mirrors are adjusted during observations in order to correct for atmospheric effects and preserve the image quality. Most large telescopes have historically been built with spherical domes whereas the NTT and TNG use an octagonal enclosure which is designed to reduce turbulence due to air passing over/through the telescope structure which again results in a better image quality. These technological advancements have been applied to, most notably, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at Paranal Observatory in Chile (just a few kilometres away from NGTS!).

Finally, I’d like to thank the Royal Astronomical Society who kindly provided financial support to help me go on this trip. I had an amazing time and learned a lot about how astronomical observations are actually done, which will no doubt be a useful skill in my future career as an astronomer.

Subject to Candidate to Planet: The Task of Zorro

If we’re confident that there is a real transit signal coming from a given star, we can apply for an allocation of time to use the Zorro speckle imager on the Gemini South telescope (which is a huge 8-metre telescope in Chile). This instrument takes lots of images of the star in quick succession, which allows us to “freeze out” the effects of the Earth’s atmosphere that causes light from stars to be distorted (similar to the distortion that causes stars to twinkle). This allows us to determine whether there are any nearby stars that might be contaminating our measurements. If a star were close enough that some of its light was “leaking” into our measurements of the candidate then we’d see a smaller transit depth than is actually the case. This would mean that we’d be underestimating the radius of the orbiting body which could mean that what we believe to be something the size of a planet could actually be the size of a star!

Below is a plot showing real data from the Zorro instrument on Gemini South for one of the most promising planet candidates from Planet Hunters NGTS (Subject 69654531 which you can read more about by clicking this link). The two different lines show data for two different wavelengths of light. The human eye typically sees light with any wavelength between 380 and 750 nanometres, but telescopes can focus on ranges centred around specific wavelengths with various filters. In this case, the telescope splits the beam of light (with a component called a dichroic) so that redder light (centred on 832 nm) goes to one camera while bluer light (centred on 562 nm) goes to the other. These two different measurements are shown in red and blue respectively on the plot below and allow us to obtain simultaneous two-colour imaging of the target.

The horizontal axis of this plot shows angular separation from the star in arcseconds, which is a unit used to measure the distance between points in the night sky (e.g. the Moon distance from one side of the moon to the other as you look at it from Earth is 1,900 arcseconds). The vertical axis is called “contrast” or “magnitude difference” and indicates how much dimmer the region around the star is compared to the star itself in units of apparent magnitude. What this plot shows is that between 0.1 arcsecs and 1.2 arcsecs, there aren’t any stars with an apparent magnitude within about 5 magnitudes of the target star’s brightness which lets us know that there probably isn’t a nearby star at these separations (although there could still be something really close in!). Using the results of these observations, we can be more confident that the transit we’re observing is “on target” (i.e. coming from the star we think it is) and we can have a more confidence in our estimates of the radius of our planet candidate as we know the levels of contamination aren’t significant. This gives us the necessary belief to push ahead with further follow-up observations which I will describe in the next part of this blog post series.

From subject to candidate to planet: Checking in with TESS

Once we have identified an object as a potential planet candidate from the NGTS data, the first step is to check whether we also see the transit signal in data from the Transiting Survey Exoplanet Satellite (TESS). Let’s walk through an example of one of the subjects that we initially thought was a planet candidate, Subject 69693101. The Planet Hunters NGTS light curve for this object looks promising. Also the odd/even and secondary eclipse (not shown) light curves look fine too and when we analysed the NGTS data we estimated a radius of 1.35 Jupiter radii for the orbiting body, which is big but not so big that we would immediately rule it out.

Therefore, we decided to check the TESS data for this star. Luckily TESS has observed this star in two “sectors” which means we have approximately 2 months worth of data to look at (TESS observes a region of the sky, called a sector, for a month at a time before moving on, but has is now revisiting regions to gather more data). The plot below shows the light curves for both sectors with the x-axis showing time in days since a fixed date. (Astronomers like to use a unit called Julian Days which is the number of days since January 1st 4713 BC, but this number is huge so we subtract standard values to make the numbers more manageable, in this case we’ve subtracted 2457000 days).

At first look, this star looks to be very variable, possibly due to some intrinsic stellar variability although periodic signals like this can be as a result of it being a binary star system. The first step is to try phase folding the data onto the period found by NGTS. This is a process where we take each section of the lightcurve that corresponds to (what we believe to be) one orbit of the candidate, centred on the transit, and plot the data on top of each other. This means that the transits should all be in the middle of the plot. The plot below shows the data folded onto the 2.51 day orbit that NGTS detected, with grey points showing the raw data and red points showing the data binned in 10-minute averages.

This looks like a clear transit signal, although the apparent variability of the star made me cautious when looking at this. Therefore, I tried folding the data to twice the detected period and, voila, we can clearly see two transits of differing depths which tells us that this is indeed an eclipsing binary system and not a planet candidate. While it’s unfortunate that this particular candidate isn’t a planet, it does mean we can focus our time and resources on more promising candidates that might really be planets!

From subject to candidate to planet: Processing all that data

You may be wondering how a subject goes from being one of thousands of subjects in the Planet Hunters NGTS project to becoming a candidate and then, hopefully, a bonafide planet! In this series of posts I hope to shed some light on the life cycle of a Planet Hunters NGTS subject.

Once a set of subjects are “retired” from the site, which occurs when all the subjects have received responses from at least 20 unique users, the data is collected from a huge “csv” file (that stands for comma-separated values). This contains every response by every volunteer for every subject included in the project and is effectively a giant spreadsheet, albeit one with millions of rows that would crash any standard spreadsheet viewer like Excel. This huge file is processed by a computer program and the most important data is pulled out and inputted into a large database that forms the hub of our operation.

From here, I can run another program that iteratively calculates scores for each subject for each possible response and computes weights for each user so that we can pay more attention to the classifications that identify transits more easily and therefore pick out subjects with high scores that might have been missed with simple vote counting. This is similar to the scoring and weighting schemes used in the Planet Hunters and Planet Hunters TESS projects, as well as many other citizen science projects. This lets me generate a list of the most promising candidates (e.g. subjects that are probably U-shaped) which are what you’ll see in the Secondary Eclipse & Odd/Even Transit Checks. I can then apply a similar program to classifications in these workflows to identify the subjects that are most likely to not have secondary eclipses or transit depth differences. These are the strongest candidates for being planetary transits instead of eclipsing binaries.

The next step is the most arduous as I look through all these candidates by eye (and there’s usually a lot of them!) and pick out the most promising ones to get a second opinion on. Filled with optimism and with candidates in hand, I show these to the NGTS team who evaluate them as a group to pick out the most promising planet candidates that we think are worthy of further investigation. At this point we would class these objects as potential planet candidates, although they can be ruled in or out through a series of tests using different data sources that I will go into in later blog posts.

Planet Hunters NGTS: A mysterious festive transit

We’ve spotted another transiting object around a star! With unprecedented image resolution we have captured the transit of this festive phenomena seen in the animation below.

The transit has a depth of ~6.5% around this small star that has a radius of only 0.4 Solar radii. That means that we can estimate the size of the transiting object (assuming a spherical Santa) to be R = 9.73 x 0.4 x sqrt(0.065) = 1 Jupiter radius! There were hopes that this would be an Earth ana-yule-logue with a Jingle Bell Rock-y composition but it seems to be a Ho-Ho-Hot Jupiter. The shape of the light curve is more similar to an exo-comet which means that it must be accompanied by an exo-cupid. Further observations will be required to identify additional exo-reindeer. Following its confirmation the festive object has been given the moniker HAT-P-Christmas.

Thank you to my fellow PhD students: Joe Murtagh, for drawing the silhouette of Santa and his reindeer; Lucy Dolan and David Jackson, for their festive-themed exoplanet puns. Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays to all!

Planet Hunter NGTS at the UK Exoplanet Meeting 2022

This week, I was in Edinburgh for the UK Exoplanet Meeting 2022 (UKExom22, for short) where I presented details of the project and the results so far from Planet Hunters NGTS, including details on our 4 new planet candidates. This was an opportunity to showcase the brilliant work of the Planet Hunters NGTS volunteers to an audience of over 100 exoplanet astronomers based in the UK, as well as a chance to meet (in some cases for the first time!) and speak with members of the NGTS team who have been working hard to help us vet the best candidates from the project and coordinate follow-up observations.

The first day of talks included some exciting results from the new JWST mission as well as techniques being employed to try and detect Earth-analogues which are currently difficult to find due to stellar activity! Later in the afternoon, I gave a 12-minute presentation describing why citizen science is so great, how Planet Hunters NGTS works and what we know so far about our new planet candidates. There was plenty of interest in the project from the audience who were impressed by both the enthusiasm of the Planet Hunters NGTS volunteers and the fact we already have four new planet candidates from our very preliminary analysis.

Day two of the conference started with more interesting talks including hearing about the current status of the PLATO mission and the results of the ASTEP telescopes that are helping the hunt for exoplanets at an observatory out in Antarctica! The relaxed schedule of the afternoon provided the opportunity for me to meet with another member of the Planet Hunters NGTS team, Sam Gill, who can fit the NGTS data with better models than the initial search to provide us with more accurate estimates of the planetary radius. Below is an image of the output of Sam’s work, showing more plots of each transit and the phase folded light curve fitted with a more accurate model. I was also able to speak with Matt Burleigh and Alicia Kendall, collaborators from NGTS who obtained more photometry of some of our candidates discussed in the previous blog post and will be able to combine data from multiple data sources to provide us with a more accurate radius estimate for Subject 69654531.

It’s not all about science at a conference as Tuesday evening saw many make the short trek up Blackford Hill which is home to the Royal Observatory Edinburgh and provides excellent views of Edinburgh Castle, Arthur’s Seat and the sunshine on Leith. The conference dinner and a trip to a Karaoke bar that had a large number of astronomers attempting to sing Bohemian Rhapsody capped the second day of the conference.

The final day of the conference included talks on improved techniques for measuring the radial velocity of stars which will allow more accurate measurements of exoplanets and the first direct detection of planetary material being accreted by a white dwarf. This discovery was made by detecting 5 (yes, only five!) X-ray photons being emitted by a white dwarf which was then determined to be due to remnants of a planet falling into the atmosphere of the white dwarf.

That brought to an end my first in-person UK Exoplanet Meeting and I’m already looking forward to next year’s meeting that will be hosted by UCL in London! In the meantime, I’ll be vetting more candidates from the project and coordinating follow-up observations as well as considering applying for additional observing time that would potentially help us get closer to validating or confirming some of the candidates already mentioned or any others that we find in the coming months. Keep an eye on the blog to stay tuned!

Planet Hunters NGTS: More detail on our first four Planet Candidates

You may have seen my previous post announcing that we have 4 new planet candidates discovered by Planet Hunters NGTS, if not you can find it here. We wanted to give you some more information on what we know about each candidate so far and the efforts we’ve made to gather follow-up data as we work towards ascertaining whether or not they’re real exoplanets! The first step once we decided that these candidates were worthy of further investigation was to fit the data using a more intricate model. This is typically what’s meant by phrases like “modelling estimates” or “fit results” that you may see below or in other pieces of science communication. Each of these candidates pose their own unique challenges in being able to confirm whether they’re really planets, however to already have 4 planet candidates is a promising sign for the future of the project and a real testament to the brilliant work put in by you, the Planet Hunters NGTS volunteers.

Subject 69695263: This is our most promising candidate so far as the transits look quite clear and our modelling estimates give encouraging results. We think this is a hot Jupiter orbiting a “K dwarf star,” which is a star slightly smaller and cooler than our Sun. We’ve estimated that the planet candidate has a radius equal to 1.09 times the radius of Jupiter, which we write as Rp=1.09 RJup. It orbits its host star every 1.74 days which means by the time you turn 18 Earth-years-old, you’d be almost 3800 years-old on this planet candidate (if it exists, and assuming you could live on it, which you can’t). We have received data from the Zorro team for this candidate (read more about the Zorro instrument and our follow-up efforts here), and it shows that the host star is isolated from other stars as far as we can tell, which means that we can be slightly more confident that this isn’t a false positive signal caused by an eclipsing binary! There’s still plenty of work to do before we can approach the possibility of confirming or validating this as a planet, but we’re cautiously optimistic about this candidate.

This candidate has been causing something of a headache since we only managed to observe one full transit and a number of partial transits (i.e. we only see the start or end of the transit). We have estimated that the potential orbiting body has an orbital period of 3.97 days however our radius estimates range from Jupiter-sized up to a radius not much smaller than our Sun. This suggests we could have a planet candidate but it could also be what’s known as an eclipsing binary with low mass (EBLM). While these are interesting systems, they’re not the planets we’re looking for! We do have Zorro data for this candidate and we can’t see another star nearby however it’s possible that the signal could be a false positive caused by “systematics” which is a general term for any trend in the data that might not have been accounted for during processing.

Much like the candidate above, this candidate is a troublesome one. The transits appear to be grazing (check out this post for a description of grazing transits) which makes it tricky to get a good estimate of the radius of the candidate. The radius of the planet candidate is estimated to be at least Rp=1.50 RJup which is already at the upper limit for what we believe can be a planet. Our upper estimate of the radius is one solar radius, meaning this could be a standard eclipsing binary. Sadly we don’t have Zorro data for this candidate to be able to check this just yet. This candidate, and the previous one, will require some more investigation to really understand what they actually are.

Lastly, this candidate is very exciting because if our initial estimates are correct, this would be one of only a handful of discoveries to date of giant planets orbiting close to their small host star. The transit depth of ~12% is much deeper than we typically expect for exoplanet transits, however the host star has a radius equal to only 1/3rd the radius of our Sun. Therefore, we believe this could be a hot Jupiter, with a radius of Rp=1.13 RJup, orbiting an M dwarf star on a 2.10 day period. These types of systems are very rare and really surprising to find because our current understanding of how planets form suggests that such a large planet shouldn’t be able to form around such a small star because there simply shouldn’t be enough time for it to form or planet building material available. The Zorro data for this candidate is also encouraging as we see no companion stars. We hope to gather more data on this object in the coming months if possible, so stay tuned!

These four NEW candidates are really exciting! They weren’t spotted in the initial check of the data by the NGTS team which means that the Planet Hunters NGTS project has proven it really has the potential to be a complimentary search to help NGTS discover as many planets as possible. We couldn’t have done this without the help of everyone who’s classified subjects on Planet Hunters NGTS and we’re eager to see what else you can help us find in the future as there are still plenty of subjects to be classified! I’ll be presenting these candidates next week at the UK Exoplanet Meeting in Edinburgh before checking the latest results from the project for more possible planet candidates. We’ll also be starting to write up the first results from the project into a paper to be submitted to an academic journal!