Turning a planet candidate into a bona fide planet

Today we have a guest post by Tom Barclay, Tom is a member of the Kepler team and also a collaborator and co-author on our second Planet Hunters paper. Tom is a research scientist supporting the work of the Kepler mission. He got his Ph.D from University College London in the UK before moving to NASA Ames Research Center in California where he spends time improving the quality of the Kepler data products, finding new planet candidates and supporting the wider astrophysics community.

The Kepler team have found several thousand exoplanet candidates. The number of targets showing transit-like signals is increasing on a nearly daily basis as we search through light curves. However, these candidates are just that, candidates. Even though the planet candidates list is thought to have a high degree of fidelity, meaning that the vast majority of candidates are indeed real planets (somewhere in the region of 90%), it requires significant amounts of time and resources to turn a planet candidate into a planet.

I’ll start by being careful with my terminology. The Kepler team use two terms when deciding a candidate is a planet. Confirmation and validation. The former generally only used when we have spectroscopic radial velocity follow-up observations. These are measurements of the wobble induced on the star by the mass of the planet. The planet and star orbit a common point in space. When the planet is moving towards us the star moves away, and vice versa. When the star moves away it gets a little redder and when it moves towards us it get a little bluer. We measure these shifts and it tells us how fast the star is moving in along out line of sight.

Radial velocity measurements in combination with a transit give the planet’s mass and radius. A radial velocity detection of a planetary mass object (normally taken to be less than 13 Jupiter masses) is very unlikely to be erroneous and we are therefore happy to confirm the existence of a planet.

In order to measure a radial velocity a planet must be close enough and massive enough to have a measurable effect on the star. The best instruments currently available are sensitive to a periodic change in radial velocity of around 1 m/s and even getting this precision requires a bright star. The Earth causes a radial velocity pull on the Sun of around 10 cm/s, measuring with this precision is out of the question with currently available instruments. We therefore require another method to use another method if we want to turn small planet candidates into planet.

Validation of a planet

Validation of a planet applies when we use a statistical argument to say that it is much more likely that the transit signal is caused by a planet passing in front of the the target star (I’ll call it star A) that it is to be caused by something else.

There are 4 main ‘something else’, or false positive, scenarios we consider.

- A background eclipsing binary

- A background planetary system*

- An eclipsing binary physically associated with the star A

- A transiting star-planet system physically associated with star A (***There is some debate on whether a planet orbiting a star other than star A should really be considered a false positive. It is still a planet but it does contaminates our statistics on how many small planet are in the Galaxy.**)

A background eclipsing binary is a system of two stars that are appear fainter than star A, usually because they are far away (although they could be intrinsically faint stars which are, counter-intuitively, in the foreground between us and star A). The two fainter stars pass in front of one another much like a transiting planet does and cause a periodic dip in brightness. Because star A is much brighter than the eclipsing system, the eclipse depth appears to be much shallower than it really is and hence the eclipse looks similar to planet transiting star A.

A background planetary system is much the same as scenario (1) but the fainter system contains a star and a planet instead of two stars. If we think the transit is of a planet around the larger star A, we get the planet radius wrong. If we are not careful this scenario could cause us to claim a Jupiter-sized planet is Earth-sized.

Scenario (3) is what is known as a hierarchical triple. There are three stars in the system, star A and two lower mass stars which eclipse each other and orbit around the same center of mass as star A. This is more common than one would initially think guess. Around half of all stars are members of binary systems and in the region of 10% of these are triple or multiple star systems. The light from star A washes out the eclipse of the smaller stars and the eclipse looks much more shallow than it intrinsically is.

Finally, there is the case where a star-planet system orbits star A. The depth of the transit is decreased by the presence of extra light from star A and we get the planet radius wrong.

We try to obtain high resolution images using fancy techniques like adaptive optics imaging which changes the shape of one of the telescope’s mirrors to correct for the movement of the air in the atmosphere. These images allow us to see very close to the star and therefore look for other stars nearby in the image that could cause the transit-like signal. Typically if we don’t see star nearby star A we are able to say there are no stars further than 0.1 arcseconds away (0.00003 degrees) which could cause the transit-like signal. We are then able to make use of models of our Galaxy to predict the probability that there is a star in the right brightness range and within the allowed separation from star A that could mimic the transit signal. It is common for us to be able to say there is less than one in a million chance of a there being an allowed background star. When we take into account the probability that a background star is an eclipsing binary or hosts a planet the result is usually that it is very unlikely that there is a background eclipsing binary or star-planet system.

Ruling out a physically associated star-planet or eclipsing binary system can be much more challenging. We can again use the high resolution imaging but it is much more likely that a companion star is very close to star A than is the case for a background star. One thing on our side is that the shape of the transit can be used to rule out a stellar eclipse: eclipses are usually much more ‘V-shaped’ than the typically ‘U-shaped’ planet transit. We can often say that we cannot fit the shape we observe with a stellar binary. It is also possible to rule out planet transits around a smaller star because the timescale of the ingress and egress (the part of a transit where the planet is moving into and out of transit) does not agree with the transit depth as both these piece of information yield the planet radius. However, we really need good signal-to-noise in order to place firm constraints on the ingress and egress durations. Even so, it always gives us some information even if it is not particularly constraining and this can be used to calculate a false positive probability.

The final step is to sum up the combined false positive probabilities from the different scenarios and compare that to the probability that the transit signal is due to a planet transit around star A. If the transit scenario is much more likely (say 1000 times more likely) than a false positive we claim the planet is validated. On other occasions we have to hold our hands up and say we can’t rule out the false positive scenario with a high enough degree of confidence and the source of the signal remains a planet candidate.

The case where stars host multiple planet candidates, such as that found by the Planet Hunter in the paper by Chris Lintott, is a particularly interesting one. This is because the probability that the a multi-planet candidate system contains a false positive is much lower than for single planet candidates system, somewhere in the region of 50 times less likely. This makes validation much easier.

Planet Hunters have already shown they can find these multi-planet system. Keep searching a more will appear, especially long period ones. There is a good chance that there is an Earth-like planet hiding somewhere in the data currently available.

Closer to Home

As I write this blog post, the transit of Venus is ongoing, with Venus finishing its slow march across the face of the Sun in less than an hour. The next time this will event will come around will be well after out life times in December 2117. The internet has been abuzz with these breathtaking images of the transit from all over the world from space telescopes,ground-based telescopes, even iphones strapped to solar eclipse glasses(!). I wanted to share my impressions of the event and how that ties into what we do at Planet Hunters .

For me personally, I wasn’t expecting to see the transit of Venus from New Haven. Yale’s Leitner Family Observatory was planning events, but it was cloudy starting in the morning, and it was predicted to be that way all day. I still packed the eclipse glasses, that I had gotten from the conference in Japan that I was at a few weeks back (the conference ended the day before the annular solar eclipse), in my bag before heading out this morning. I was hoping but not holding my breath for there to be a clearing of the clouds later in the afternoon, but it had rained midday. The clouds were thinning a bit in the afternoon, teasing with some small glimpses of the Sun or a brief moment where the sunlight could be seen trying to peak through. I remember on one of my first observing runs, when the weather was bad talking to the lead observer, the older graduate student in my research group. I remember her telling me about sucker holes in clouds, holes in the otherwise thick cloud cover. They happen, but not go to chasing them with your telescope because the can close and move just as fast as they appeared. I was hoping maybe we’d get a clearing in the clouds but it didn’t look like it was going to.

I was already resided to the fact I was going to be watching online on the live streams. I had even lamented to Chris who’s in Norway, in the land of the midnight Sun, for the transit who also had clouds from horizon to horizon for the start of the event. I got on the bus to go home, and noticed what I thought was sunlight on the buildings. I got off a few stops later so I could walk the rest of the way home (or to the observatory just in case), and low and behold – a sucker hole had opened and there was the Sun struggling but nearly all the way out of the clouds staring back at me right above the astronomy building. I pulled out those eclipse glasses and my own eye glasses (that I rarely wear) and there it was. A bit of cloud still coming over in waves across the Sun’s disk, but there was a black spec on the top right. That was Venus! I made it to the Leitner Observatory where the other postdocs and grad students were, sharing our eclipse glasses to the members of the public who had come to the event and were in line to see through the solar telescopes. We also also got a chance to see the transit through solar telescopes. I captured a neat image from a solar spotter that an amateur astronomer (and also a fellow Planet Hunter) had kindly brought along. As the sun set, the clouds came back as quickly as they had parted and the sky was covered and grey again.

I have to say it was truly breathtaking and I hope you got to see it yourself and if you didn’t see it outside that you were able to view the transit online. It is amazing to think that that small dark sphere is really a planet moving in front of our Sun.

One of things for me that is so fascinating is how our view of exoplanets has changed since the last transit of Venus, which occurred in 2004. Kepler hadn’t launched, we didn’t have over 2000 transiting planet candidates (or Planet Hunters 🙂 ) Kepler really has changed how we view the universe around us, with extreme worlds orbiting two stars as well as the first detection of Earth-sized planets, and the first set of planets orbiting in the habitable zone of their stars (meaning if they were rocky or had rocky moons they might be able to have liquid water pool on their surfaces).

The same way that Venus is blocking out part of the Sun’s light (about 0.1%), is the way we identify planets in the Kepler light curves with Planet Hunters. If aliens in another solar system could watch the Sun today/yesterday, they would see a drop in light of about 0.01% for nearly 7 hours indicating Venus’s presence. We see the drops in the light curves indicative of a planet orbiting their parent stars in the Kepler field. We’ve already found four new planet candidates that weren’t previously identified by the Kepler team but there’s something different in seeing the light curve compared to seeing the Venus transit live. I’ve always known these planet candidates we’re finding are marching across the disks of their parent stars, but seeing the transit of Venus it felt real. I’m heading back to spend the rest of the night working on my next Planet Hunters paper, thinking about the transits and planetary systems we’re finding and it feels just a bit more familiar…..a little bit closer to home….

~Meg

PS. Fancy looking for some more transiting planets, come to the Planet Hunters website and give it a try.

Assessing the Kepler Inventory of Short Period Planets

You might remember that I’ve been working on a systematic search of the Q1 light curves to examine the frequencies of large planets (> 2 R⊕ -Earth radii) on orbits less than 15 days. I’m happy to announce that my paper titled “Planet Hunters: Assessing the Kepler Inventory of Short Period Planets” has just been accepted to Astrophysical Journal. The paper is available on-line here if you’d like to read it (warning: it’s quite long coming in at 22 pages of single spaced text, 13 figures, and 8 tables!), but I’ll give the highlights below.

We wanted to see for Q1 light curves, how well we could find planets and what might be left remaining there to be found compared to the known Kepler sample of planets. I think this important because Planet Hunters can serve as a separate estimate of the planet abundance and Kepler detection efficiency. I decided first to concentrate the search of planets with periods less than 15 days so that I was certain there would be at least two transits visible in the Q1 light curve. I thought it might be harder for us to identify transits if there was only one dip, so I thought it would be a good idea to start where there were at least transits.

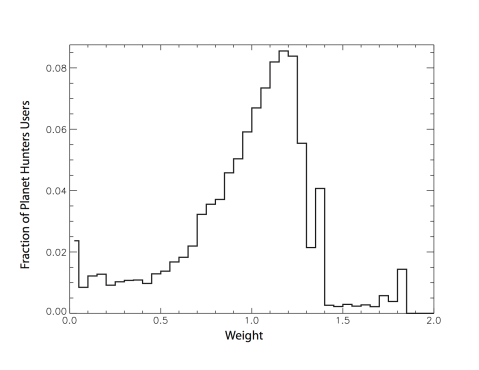

To figure out which of the light curves had transits, I developed an algorithm to combine the multiple classifications for each light curve (for Q1 on average 10 people classified each ~33 day Kepler light curve) by developing a weighting scheme based on the majority vote. What the weights are doing is really just helping me pay a bit more attention to those that are a bit more sensitive at finding transits when combining the results from everyone who classified that light curve. The weighting scheme makes us more sensitive to transits than if I just took the majority vote for each light curve and helps to decrease the false positives. Below is the distribution of user weights for Q1 classifiers.

Using the user weights, I am able to give each light curve a ‘transit’ score (the sum of the user weights who marked a transit box divided by the sum of the user weights for everyone who classified the light curve). To narrow the list from 150,000 light curves, I picked those light curves that had ‘transit’ scores greater than 0.5 as my initial list of candidates. I applied several additional cuts to widdle down the list (you can read all about those details in the paper). That left about 3000 light curves and approximately 4000 simulations to go through. So to identify those that had at least two transits in them, we turned to a second round of review where light curves were presented in a separate interface and volunteers were asked whether they could see at least two transits (ignoring the depths being the same or not) in the light curve and asked to answer either asked to answer ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ to the question. Those light curves where the majority of classifiers said ‘yes’ were moved on to review by the science team. A big thank you to everyone helped out with the Round 2 review; your efforts are acknowledged here. As always we acknowledge all those who contribute to Planet Hunters science on our authors page.

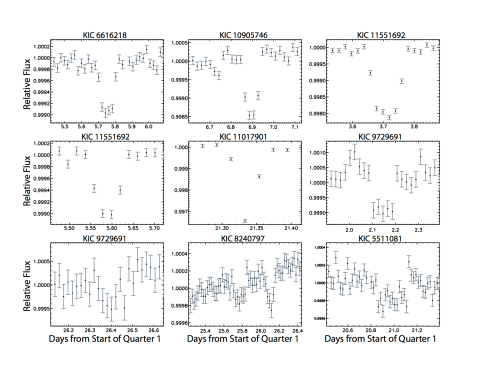

At the end of the search after removing all the known planet candidates and transit false positives known before February 2012, there were 7 light curves that have transit-like events but not on the original Kepler candidates list published back in 2011 that used only Quarters 1 and 2. I show example transits from each of these 7 light curves in the Figure below. One of these light curves turns out to be one of the candidates from our first paper and another one was part of our co-discoveries with the Kepler team. Even those these 7 light curves weren’t found in the first Kepler candidate releases, they now have been found in the latest iteration of the Kepler candidate list released earlier this year, where they’ve used an updated and improved versions of their detection and data validation pipelines. So what that shows is that the Kepler detection and validation processes has indeed gotten better, but there’s more that we can say.

Zoom-in of selected transits for each set of transit identified visible in short period candi- date light curves remaining after Round 2 review and visual inspection. Visually the science team could identify two separate sets of repeating transits in the mutli-planet KIC 8240797, 9729691, and 11551692 based on the user drawn boxes We note that the snapshot of KIC 8240797 contains two independent transit events.

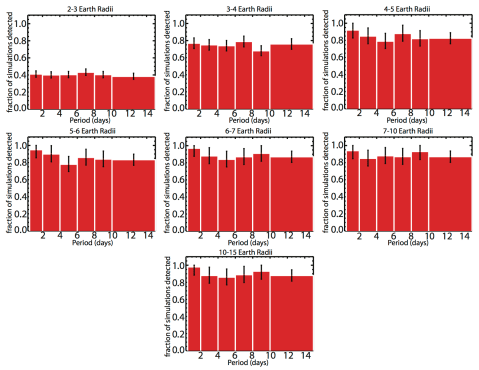

Now that we know what new things we found, and that there wasn’t anything more than the 7 candidates that are now KOIs on the latest Kepler candidate list, we can look at what that says for the completeness of the short period planet inventory. Using the simulations that you’ve helped classify, I was able to look at how good Planet Hunters is at detecting planets of different sizes on orbits less than 15 days. I randomly selected about 7000 light curves that at the time weren’t known to have transiting planets or were not eclipsing binaries and inject synthetic transits into them for varying planet radii (ranging from 2- 15 R⊕) and periods less than 15 days. The simulations are really important because one completed I could see what which of the simulations made it to the end of my candiate pipeline and which ones didn’t. Having the results from those classifications really made the heart of the paper, because we could show independent of the Kepler planet candidates and detection and validation processes, what we were sensitive to.

Efficiency recovery rate for simulated planet transits with orbital periods between 0.5 and 15 days and radii between 2 and 15 R⊕.

What was striking to me, was our detection efficiency is basically independent of orbital period and that whether there were 2 or 15 transits in the light curve, they were just as easily identified. I think this bodes well for us being just as sensitive to single transit events (I’m starting to work on testing that now). Although performance drops rapidly for smaller radii, ≥ 4 R⊕ Planet Hunters is ≥ 85% efficient at identifying transit signals for planets with periods less than 15 days for the Kepler sample of target stars. For 2-3 R⊕ planets, the recovery rate for < 15 day orbits drops to 40%. I compared to the Kepler planet candidates and found similar results (which is a good check).

Our high recovery rate of both ≥4 R⊕ simulations and Kepler planet candidates and the lack of additional candidates not recovered by the improved Kepler detection and data validation routines and procedures suggests the Kepler inventory of ≥4 R⊕ short period planets is nearly complete!

Awesome People: More from ZooCon1

Today we have a guest post by Jules, fellow Planet Hunter and zooite who attended the ZooCon1. Jules is a lead moderator and blogger for the Solar Stormwatch and Moon Zoo forums as well as a volunteer on the Zooniverse Advisory Board.

Just back from the very first #zoocon1 in Chicago. I attended as a volunteer on the Zooniverse Advisory Board. As Meg said it was a chance for the science teams from new projects to meet with and learn from representatives of current projects and for everybody to meet up with Zooniverse techies and developers. It made sense then for some of the “old hands” to present an overview of their own projects. Meg’s Planet Hunters talk was particularly interesting as it highlighted the value of Talk and the great collaborative work being done there by volunteers.

A brief foray into data reduction showed the kind of work necessary to make the clicks usable. For example, there are 5,508 stars with possible transits. Removing all pulsating stars, which can be mistaken for transits, reduced the number of candidates to 3,404. Further examination of these transits reduced the pool further to 77 transit candidates – a much more manageable number.

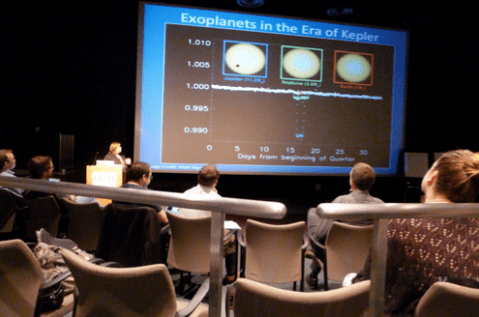

Here’s Meg in action demonstrating the light curves of different sized planets.

The discoveries Meg highlighted included a slide showing 4 planet candidates missed by Kepler one of which is being re-investigated because of the work done by Planet Hunters. Kepler 16, the circumbinary system, also got a mention as did the impressive volunteer-led analysis on cataclysmic variables and heartbeat stars.

Old Weather, Mergers and the Milky Way Project were also put in the spotlight. Afterwards someone from one of the new projects told me how amazed they were that volunteers would want to do more than just click and another told me that they found the Planet Hunters story particularly inspiring and wanted to know how Planet Hunters had attracted these “awesome people.”

Well that’s Citizen Science for you. Volunteers come with a great mix of interests, skills and the knack of finding treasure!

Update on Dwarf Novae

Today we have a guest post by fellow Planet Hunter Daryll (nighthawk_black) updating us on the search for dwarf novae and cataclysmic variables. Daryll’s here to talk about a dwarf nova candidate found in PH Talk.

Hi Planet Hunters,

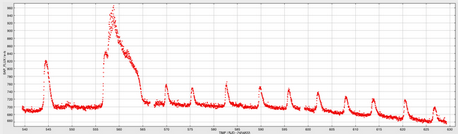

Following the guest post from GO Director Martin Still, a review of light some light curves discussed on PH Talk turned up an interesting target somewhat similar to the serendipitous Dwarf Nova known as NIK 1. First noted by myself and several volunteers as a possible cataclysmic, we believe this to be another SU UMA type variant with over 50 quasi-periodic brightness changes observed and a defined superoutburst, in the public Q6 data.

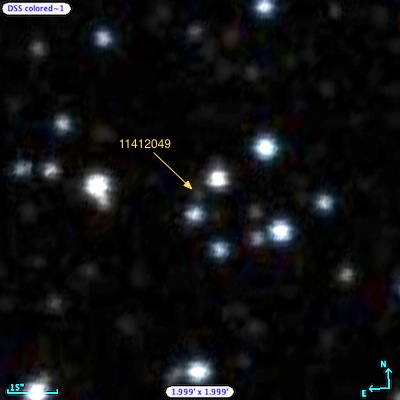

The activity is not visible in all quarters. An examination of the accompanying target pixel files (these are files created by the Kepler processing pipeline that show the brightness over time for each of the pixels that are added up to make a Kepler light curve and those surrounding that don’t go into making the light curve – they can help you see if the features in the Kepler light curve come from the target star or something nearby that is contaminating the target’s star aperture) reveal that the true source of the dwarf nova candidate lies in the background and likely originates from an adjacent source tagged as KID-11412049, leaving how much activity we see in the original light curve dependent on the differing aperture pixel masks used for each Quarterly roll. Unfortunately it does not appear to be an eclipsing arrangement nor has it displayed any transiting circumbinary companions.

We asked the science team to take a look at this star and they think it looks like a good dwarf nova candidate. The PH science team has applied for Directors Discretionary Time seeking additional observations in the coming Quarter (we’re all waiting to hear back if the Planet Hunters proposal has been approved) to learn more about this system including its outburst supercycle, accretion disc stability and component compositions. Early analysis indicates high mass transfer with a notably short orbital period of 76 minutes; a GALEX survey shows this location also appears to be associated with a UV source.

Screening out background binaries from transit candidates is something the community has gotten pretty sharp at and I believe more of Martin’s missing Dwarf Nova will turn up. If confirmed, this will be the 5th Superoutbursting DN in the Kepler FOV and the 17th total, so well done and keep up the eagle-eyed hunting!

Zooniverse Science Conference

Greetings from Adler Planetarium in Chicago. I’m at the first Zooniverse Science Conference. I’m here representing the Planet Hunters science team. At this conference science teams from the current and upcoming Zooniverse projects and the Zooniverse development team have gathered together to talk citizen science. It’s been a great two days of presented talks and discussions. This is the first time that teams from across the Zooniverse projects have come together. I’ve really enjoyed talking to the scientists from the different projects, and what I’ve been really impressed with is the cool and wide-ranging science that is being done in the Zooniverse. I’ve been hearing about the exciting future projects and new tools and features the Zooniverse is working on. This morning I shared the highlights from Planet Hunters and how I’m going from clicks to planet candidates. It was great to highlight all the science we’ve done and will be doing in the future with your classifications on Planet Hunters. I focused on my search for short period planets from the Quarter 1 classifications (on a side note – I got a response from the referee for my paper. I’ve revised the manuscript and the paper is back with the referee. Hopefully soon it will be accepted for publication by the Journal).

Cheers,

~Meg

Searching for Earthlike Worlds

Today’s post is a guest post by Tony Hoffman. He’s a fellow Planet Hunter and is also one of our Planet Hunters Talk moderators. Today he’s writing about the public talk Planet Hunters PI Debra Fischer gave at the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York.

On March 30, Planet Hunters’ own Debra Fischer, professor of astronomy at Yale University, gave a talk on “Searching for Earthlike Worlds” for my astronomy club, the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York, at the American Museum of Natural History’s Kaufmann Theater. The talk was both informative and inspirational, expanded my perspective on the science of exoplanetology, and left my head spinning with the discovery possibilities that the next decades may have in store.

Dr. Fischer covered 6 broad topic areas in her talk: our place in space in time; exoplanet discovery techniques; the importance of finding many Earthlike worlds; how do we know if a planet is “habitable” enough; how our solar system compares with others we’ve found; and astronomy as a vision plan for life on Earth.

Our Place in Space and Time

Debra started with our own solar system, describing the (now) 8 planets and other bodies, and how Earth is the only habitable world among them, and then quickly zoomed out, with the Sun as one of billions of stars in our galaxy, and the Milky Way one of billions of galaxies. “We’re such a tiny speck in a vast universe,” she said.

As to our place in time, she evoked Carl Sagan’s cosmic calendar, a measuring stick in which the age of the universe is compressed into a single year, to try to put the time scale of the universe in human terms. In it, the Big Bang occurred as the New Year began, and we’re waiting just as the clock is about to tick over into a new year. In this scenario the Milky Way formed in May, the Sun and its planets in August. The dinosaurs arose on December 25 and went extinct on December 30. All of human history would have taken place in the last hour or so. Fischer marveled at the human ability to study and comprehend the universe around us, and wondered what humanity might be able to accomplish if we were to have the same species longevity as the dinosaurs.

She then related a brief history of exoplanetology, describing how before the discovery of 51 Pegasi in 1995, some early planet hunters despaired of finding planets and wondered if we were alone. When 51 Peg was discovered, using the radial velocity or wobble technique (which Fischer uses in her own research), many scientists were incredulous that there could be a Jupiter-sized world orbiting its star in only 4 days—how did it survive, and how was it formed? (We now know that it formed much farther out and migrated there.)

The Birth of Planet Hunters

Debra then discussed the transit method and the Kepler project, singling out Kepler-11—the 6-planet system whose small worlds were confirmed by transit timing variations: some of the transits appeared earlier or later than expected, enabling the Kepler team to calculate the mass of the planets based on their effect on each other. She also discussed “Tatooine,” the Saturn-sized world orbiting a double star.

She related how Planet Hunters began. “We were very excited about the Kepler mission at Yale,” she said. “Kevin Schwainski, an Einstein fellow at Yale, would stand in the hallway, and every morning when I’d walk in he’d say, ‘So Debra, what can we do for planet hunters? There has to be something we can do with exoplanets. People love exoplanets.’”

“I’d sort of look at him and say “Nothing I can think of.” Then in the summer of 2010, I sent my grad students and postdocs to a Sagan summer school where they looked at the Kepler data. The way that they were studying the data was inspiring. They’d take one light curve and puzzle over it. I realized that the computer algorithms to solve these systems weren’t terribly robust, and maybe we could start a new citizen science project where we’d serve up the Kepler light curves.”

She, Meg Schwamb, and others at Yale got in touch with Chris Lintott and the Oxford team running the Zooniverse, and the result is the Planet Hunters site, with which she notes the public has found exoplanets that “…fell through the cracks in the Kepler data.” Our work here has also helped the Kepler project fine-tune its search algorithms.

Another exoplanet discovery technique she mentioned is direct imaging. So far, mostly using the Keck telescope, astronomers have imaged a couple of dozen gas giants at relatively large separations from their stars. Fischer thinks that’s just the beginning, though. “We want to be at the point some day when we can take a photograph of a star, null out the light from the star, and see those pale blue dots, orbiting.”

Hundreds of Earth

Projects like Kepler and HARPS have been detecting smaller, rocky worlds, some in or near their star’s habitable zone. In order to eventually find life-bearing worlds, it’s important that we find a large sample of potentially habitable worlds. “We want to find hundreds of Earths,” she said.

Suppose we find a super-Earth that’s 10 Earth masses. How would we know if it might be habitable? “It’s tricky because the composition of a planet can vary wildly,” says Fischer.”You really want to have the mass of the planet as well as its size, so you can start to figure out whether it’s a planet like the Earth, which has a layer of molten iron, which convects turbulently and spawns a magnetic field that protects us from the solar wind, or is it something like a super-Earth that has a heavy iron and rock mantle, that may be convecting very actively, or is it in fact a water world?”

Water is one of the most common elements in the universe, and if you have a planet in the habitable zone, it’s going to have liquid water. But water doesn’t guarantee habitability. “A lot of astronomers right now are a little bit worried,” she continued. “If you don’t have an active world with plate tectonics that shoves the land up into mountains, and has the water pooling at lower levels, you’ll just end up with a planet that’s covered with a whole skin of water. Will we be able to find life on those kinds of worlds? I think the answer is yes, but it’s probably not going to be a SETI kind of life. Electronics and water usually don’t mix very well.”

She has been very involved in increasing the sensitivity of spectrographs in the Yale Doppler Diagnostic Facility, an instrumentation lab where she works with 3 post-docs, to be able to detect smaller rocky worlds. “We don’t want to build spectrographs the way they’ve always been built. We’re trying to think outside the box. How low can we go? As we increase the resolution of the spectrograph and control all of our systematic errors, we think we can get down to something like 2, 5, 10 cm/second (instead of meters per second).”

Debra is in charge of a project that uses CHIRON, a spectrometer her team developed, to search for low-mass, rocky planets around Alpha Centauri A and B, the nearest star system to Earth. If planets are found there, she thinks that eventually humans will send space probes there—not spaceships filled with humans, but nanotechnology-inspired micro-ships more like cell phones, which can take pictures and “phone home”.

In the next decade, Fischer expects spectroscopy to be a powerful tool in helping to determine the potential habitability of the worlds we find, as astronomers look for the chemical signatures they associate with life. “What you’re going to see in the next decade is transmission spectra from transiting planets,” said Fischer. “The planet’s light also disappears when it passes behind the star. By dividing out the starlight, you can see the spectrum of the planet.”

Fischer also noted that the science is changing, borrowing and learning from other disciplines.”Exoplanet discoveries used to happen in isolation,” she said,” but now we’re partnering with biologists working to understand origins of life on our planet, and geologists, who are helping us to understand the geological processes that spawn magnetic fields, that store water, sequester water, on planets.”

How Our Solar System Stacks Up

We’ve found hundreds of planets, thousands of candidates. Most of the planets are multiple-planet systems. How many of the systems look like ours?

Statistical analysis of Kepler data indicates that there are ~1.6 planets per star (a lower limit). Around 1% of stars will have hot Jupiters, and that occurrence rate goes up if the star has more heavy elements and if the star is bigger. For Earths and super-Earths, occurrence rate is greater than 30 percent, probably 45 or 50 percent. Also, planets are prone to migrate away from the location they formed, just as 51 Peg B migrated in to a 4-day orbit. Theoreticians are convinced that planets move around all the time. In fact, there’s evidence that asteroids and comets scattered in a configuration that only makes sense if Uranus and Neptune were once between Jupiter and Saturn, and then went spiraling outward into wider orbits.

Astronomy as a Vision Plan for Earth

Fischer ended the talk by revisiting the dinosaurs, and what we as a species might be able to accomplish if we’re able to survive. “The dinosaurs were munching along as the asteroids were flying over their heads,” she said. “They had no idea. Of all the species that have existed, we are, I think, magnificent, because we are willing to look out and try to understand our place, our origin, our history, our fate. We’re the first species to be able to consider engineering solutions to some of the big threats. A lot of people say, this doesn’t seem important to me, let’s take all of that huge NASA budget—which is something like a half penny on the dollar—and use it to feed people. If you’re a business manager, you have to think about the day-to-day running of your business, but to be really successful—to be a Steve Jobs, a Bill Gates—you also need to have vision. That’s where I think astronomy plays a key role. We have vision—we’re looking out, and looking back, and understanding ourselves better for that.”

Dwarf Novae

We have a guest post from Martin Still. Martin is Deputy Science Team Lead and Guest Observer Office Director for Kepler. He’s writing today to tell you about an interesting class of objects you might encounter when classifying Kepler light curves

Kepler Gets an Extended Mission

The NASA Senior Review panel decisions are in. The panel assessed Kepler and several other astrophysics missions including Hubble Space Telescope, Chandra X-ray Observatory, Spitzer Space Telescope, XMM-Newton, Swift, Planck, Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope,and Suzaku. This is to evaluate the missions and decide if they should be renewed or approved for an extended mission. For Kepler, having launched in March 2009, the spacecraft is over 3 years old. The primary mission was to last 3.5 years with the goal to find and constrain the frequency of rocky planets and in particular Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone (the region around the star where liquid water could exist on a planet with an atmosphere similar to the Earth’s) of solar-type stars.

Kepler has been a spectacular success finding a treasure trove of over 2000 planet candidates in the first 16 months of data (Quarters 1-6), and revolutionized our understanding of planetary systems. But the Earth-sized planets are proving tricky because stars are much more variable than the Sun. This was unexpected,so instead of taking 3 years to confidently identify Earth-sized and smaller planets it will take 3 more years beyond the nominal mission. For NASA missions, you’re given the time you request when the mission gets selected to do your primary science goals and then can ask for additional funding for an extended mission. The Kepler spacecraft is in excellent health, with the only major failure being the loss of once of their science modules in Quarter 4. There is plenty of fuel to keep Kepler alive and pointed well beyond 2016, so Kepler team applied as did the other missions for funding to extend the mission another four years.

A NASA panel reviewed the mission, and the excellent news is that Kepler was approved for a 4 year extension! They also recommended to extend all of the missions it assessed which is excellent for the astronomy community. You can read the entire report here. Congratulations to the Kepler team for the success of their program and thanks for the excellent data that we’ve been finding planets and other interesting things in with Planet Hunters. This is great news! So this means Kepler will be running an additional 4 years – so a total of ~7 years of data. This means we can probe planets out at even further distances. This will be particularly interesting because we have been finding these very compact multiplanet systems (some having more several planets on orbits smaller than Mercury’s), so I’m curious to see how many multiplanet systems that have planets at distances beyond an 1 AU exist.

So what does this mean for Planet Hunters? First off it’s mean we’ll have plenty of light curves to look at for a long while with the potential to find even more interesting things and planets awaiting discovery. But what’s going to change come November, is the there is no proprietary data anymore. Currently the Kepler scientists have a first crack at the data before it is released to the rest of the scientific community and the public. Kepler is currently observing Quarter 13 but we have only up to Quarter 6 data. In Novemeber this all changes – they’ll be another big data release in July 28 (Quarters 7,8, and 9 will be released) and the next on October 28 (Quarters 10, 11, 12, and 13 will be released) . After that once the data comes off the Kepler spacecraft and is processed by the data processing algorithms the data will be released to the public and the Kepler team at the same time and we’ll be showing the light curves as fast as we can get them on the site.

This is a new era for the exoplanet community. I can’t wait for November, it’s going to be a great couple of years for Kepler and Planet Hunters if the past year has been any indication of the interesting science we’ll be able to do. In the meantime, there’s still lots of light curves to search through before the next data release and we’re starting to look for new planet candidates in those classifications from Quarters 3, 4, and 5 as well as take follow-up observations of our highest priority candidates (more on that in next the few blog posts). So keep those clicks coming.

Direct Imaging of Planets

Today we have a guest blog from Sasha Hinkley talking about a different way of detecting exoplanets than the transit method we use at Planet Hunters. Sasha is a Sagan Postdoctoral Fellow at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, CA. Sasha received his PhD from Columbia University in New York City and has been involved in the direct imaging of exoplanets for several years.

In recent years, astronomers have identified hundreds exoplanets (as well as over 2000 new candidates from the Kepler mission), launching the new and thriving field of exoplanetary science. The vast majority of these objects have been discovered indirectly by observing the variations induced in their host star’s light. The Doppler surveys detect stellar “wobbles” induced by the planets, and provide valuable information about the orbital separations, eccentricities, as well as lower limits on the masses of companion planets. At the same time, observations of planets that transit their host star, creating a brief dimming of the stellar light, can provide fundamental data on planet radii and even some coarse information about the compositions and atmospheres of these extremely hot planets. However, studying those objects out of reach to the Doppler and transit methods will reveal completely new aspects of exoplanetary science in great detail.

The direct imaging of exoplanets, i.e. actually obtaining an image of exoplanets, is a technique that is sensitive to massive planets at much larger orbital distances—larger than even the orbital distance of our Neptune. This technique is already providing a completeley new and complementary set of parameters such as luminosity, as well as detailed spectroscopic information. This spectroscopic information will provide clues to the planets’ atmospheric chemistry, compositions, and perhaps may even shed light on non-equilibrium chemistry associated with these objects. Moreover, the direct imaging of these exoplanets will allow astronomers to more fully characterize the architecture of planetary systems, especially at young ages where the radial velocity methods are hampered by the instrinsic stellar “jitter” of the stars. Observing the placement of these planetary mass companions at very young ages serves as a “birth snapshot”, lending support to various planet formation models.

The major obstacle to the direct detection of planetary companions to nearby stars is the overwhelming brightness of the host star. For example, if our solar system were viewed from 70 light years (average for a nearby star), Jupiter would appear roughly a billion times fainter than our Sun with a separation on the sky comparable to the size of a dime viewed from 5 miles away. As such, these planets are completely lost in the glare of their host star. The key requirement is the suppression of the star’s overwhelming brightness through precise starlight control.

Astronomers are currently overcoming this incredibly challening task through precise starlight control, using sophisticated instruments and observing strategies at the largest ground-based telescopes. So far, astronomers have successfully obtained direct images of a handful of exoplanets, including around the stars HR 8799, Fomalhaut,and Beta Pictoris. These studies have demonstrated that direct imaging of exoplanets is now a mature technique and may become routine using ground-based observatories. More so, we will soon see a new fleet of instruments dedicated to detailed spectroscopic characterization of planetary mass companions making these kinds of discoveries routine, initiating an era of comparative exoplanetary science.

One such instrument, the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), has been built by a consortium of American and Canadian institutions and will be deployed to the 8 meter Gemini South telescope in 2013. This instrument will survey several hundred, nearby young stars achieving sensitivities that will allow it to image planets with masses a few times that of Jupiter, and gather information on the detected exoplanets’ spectrum and any polarized light they may emit. The Europoean counterpart to GPI is the SPHERE project at the Very Large Telescope. This project, also in the Southern Hemisphere, will be a similar dedicated exoplanet imaging instrument with similar science goals as GPI. A pre-cursor project called Project 1640, on the Palomar 5m telescope is currently testing some of the techniques to be used by these projects and hopes to image exoplanets in the Northern Hemisphere. These instruments will likely obtain images of dozens of exoplanets in the next several years, and reveal completely new aspects of planetary science that we could not yet have imagined.

Image Credit: Marois et al (2010)