PH1 Paper Offically Accepted for Publication

Last October we announced the discovery of PH1 – a four star planetary system hosting a circumbinary planet (PH1b). The transits were spotted by volunteers Robert Gagliano and Kian Jek on Talk. I’m thrilled to announce that our paper “Planet Hunters: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet in a Quadruple Star System” has been officially accepted to Astrophysical Journal. Congratulations to all involved.

Now that the paper has been accepted and is in press, you can find the accepted manuscript online and added to the Zooniverse publications page (which has a total of 4 Planet Hunters in press/published papers based on your clicks). The official journal version will be published sometime in May.

PH1b is our first confirmed exoplanet discovery, a milestone for Planet Hunters. The 6.18 Earth radii planet orbits outside the 20-day orbit of an eclipsing binary consisting of an F dwarf ( 1.734 x the Radius of the Sun) and M dwarf ( 0.378 x the Radius of the Sun). For the planet, we find an upper mass limit of 169 Earth masses (0.531 Jupiter masses) at the 99.7% confidence level. With a radius and mass less than that of Jupiter, PH1b is a bona fide planet. Not all planet candidates can be confirmed as we could with PH1b. Since PH1b is orbiting an eclipsing binary, we could use the fact that there are no changes in the timing of the stellar eclipses due to the planet to constrain PH1b’s mass.

With the acceptance of the paper, we have asked that PH1b be added to the NASA Exoplanet Archive (NExSci)’s list of confirmed exoplanets . NExSci has taken on the role of being the keeper of the list of confirmed exoplanet discoveries. In addition, PH1b has bestowed the Kepler # that was saved for us in October. PH1b has been given officially a Kepler designation of Kepler-64b and added to the list of planets in the Kepler field. You can find out more about what the criteria for obtaining a Kepler # is here.

In the list of confirmed planets, the planet is referred to as PH1b (you might notice an extra space – that should be revised in an update to the NASA Exoplanet Archive). I like to think of the Kepler # as icing on the cake. We’ll still refer to the planet as PH1b. Kepler-64b will be an alternate designation and used in the catalog of planets in the Kepler field (PH1b will be listed as an alternative designation). The full data page for PH1b on the NASA Exoplanet Archive can be found here

For those who are wondering what the NASA Exoplanet Archive is, Rachel Akeson, Deputy Director of NexSci and Project Scientist for the NASA Exoplanet Archive, explains below:

The NASA Exoplanet Archive is an online astronomical exoplanet and stellar catalog and data service provided to the astronomical community to assist in the search for and characterization of exoplanets and their host stars.

Current data content and tools include:

- Interactive tables of confirmed planets, Kepler Objects of Interest (which includes the planet candidates), Kepler Threshold Crossing Events, stellar parameters for all Kepler targets in Q1-12 and a list of Kepler confirmed planet names and aliases.

- Overview pages with all available data for each confirmed planet and Kepler Object of Interest

- Tools to view, normalize, phase and calculate periodograms for light curves, particularly those from Kepler and CoRoT

- Transit predictions for all known transiting planets and Kepler Objects of Interest

- URL-based access to all table data

The archive is available at http://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu/index.html and includes links to documentation for all these services.

Making Way for Q13 Data

The Kepler field will be high in the sky starting in the next month or so and continuing over the Summer months. Thanks to all of your hard work and classifications, the science team has been writing observing proposals to ask for telescope time on the the Keck telescopes in Hawaii to follow up on our best planet candidates. We’ll learn in a few months whether we have been granted the nights. So stay tuned!

In the meantime, the team is continuing to search for new planet candidates with your classifications and Talk comments. You have been analyzing light curves from Quarter 7 released by NASA during Kepler’s primary mission. To begin searching the first data release of Kepler’s extended mission, Quarter 13, we need to finish Quarter 7. We need your help to make room for the new light curves.

As with any new data, there are now new chances to find even more planets. Let’s make the final push so that by April we could be looking at Q13 data. Please get clicking today at http://planethunters.org

Happy Hunting,

~Meg

PH1 Paper Resubmitted

Just a quick note to say that I’ve resubmitted the PH1 paper back to the Astrophysical Journal last week. Many thanks to my co-authors for their help on the revised manuscript. The paper has been received by the Journal and sent to the referee (another scientist in the field whose identify usually remains anonymous to the authors) for a second review as part of the peer review process. The changes we’ve made I think make it a stronger paper. In about a month, we should get a response from the referee. Hopefully (fingers crossed) we have sufficiently addressed the referee’s concerns and questions, and the paper will be accepted at that point. When we hear back from the Journal editor and referee, we’ll let you know.

More about the Discovery of PH2-b

The project’s second confirmed planet, PH2-b (a Jupiter-sized gas giant planet orbiting a Sun-like star), was discovered by several members of the PH community who classified the light curve and then posted the candidate on Talk. A volunteer-organized effort took this from a possible repeat of transits to a likely candidate that was then passed to the Science Team and subsequently validated as a real bona fided planet. Volunteer rafcioo28 who was the first person to mark a transit in Q4. Mike Chopin was the second and the one to first post on the Talk page about the transit in February of last year. Hans Martin Schwengeler went to look at the rest of the publicly released Kepler data months later spotting the other transits. Together rafcioo28, Mike, and Hans with the help of Abe Hoekstra, Tom Jacobs, Kian Jek, Daryll LaCourse have discovered Planet Hunters’ 2nd confirmed planet PH2-b. I’ve asked Mike and Hans (rafcioo28 we haven’t been able to contact thus far) write a bit about their thoughts on the discovery.

Artistic rendition is a hybrid photo-illustration, showing a sunset view

from the perspective of an imagined Earthlike moon orbiting the giant planet, PH2 b. Image Credit: H. Giguere, M. Giguere/Yale University

Mike Chopin

At school, at the age of fourteen, I did a project on atomic (particle) physics which gained me a grade 1 CSE. The following year I studied and passed my Physics exam which was interesting for my school since that was a subject not on the school curriculum. After leaving school, I studied OND Engineering at Kingston Polytechnic although I only completed my first year since I longed to go travelling. My wanderlust got the better of me and I joined a shipping line as a Navigating Cadet Officer. I suppose it’s easy to see why astronomy has fascinated me since knowing about stars was part of my navigation syllabus.

My childhood hero was, and still is, Captain James Cook a man I consider to be the greatest explorer of all time. I consider myself fortunate to have visited many places this great navigator charted. In 2012 his observation of the transit of Venus in 1769 was commemorated at Venus Point in Tahiti. Although I wasn’t there for 2012, I did get to Venus Point a couple of years earlier. Like Cook, I spent some time in the Navy and have a passion for boats especially under sail. I have two complete circumnavigations under my belt; the first by sea (unfortunately via the Panama Canal and not Cape Horn) the second was by air, island hopping my way across the Pacific. I have now visited ninety six countries and hope that it won’t be too long before I join the Travellers’ Century Club.

Latterly, I was employed by Lloyds TSB (Registrars) as a project officer with my principal role as the sole technical writer writing context sensitive help for software, on-line documentation, trouble-shooting guides for the IT department and interactive eLearning modules. Following redundancy, I went freelance as a writer and have had a couple of small contracts both as a writer and as a data manager.

I am delighted to have been involved with the discovery of an exoplanet, a planet orbiting a distant sun. From the outset, I enjoyed the thrill of analysing the light signals recorded and posted on the planethunters.org website. This website invites ordinary people to take part in analysis of vast amounts of data. Often called ‘Citizen Science’ this excellent website provides clear tutorials to enable the amateur to partake in this worthwhile research project.

In its simplest form, when an exoplanet passes between our line of sight and its sun, there is a reduction in the amount of light that we receive. This effect can be seen if we plot the light output from this star against time. While trying to analyse the data, I would try to imagine the planet transiting its sun, if it was a large planet and close to its sun would it cut more light than if it had been a small planet and a giant sun? Does it have a high reflectivity (albedo) and is it inclined to its ecliptic and if so, would it add or reduce the amount of light recorded. If distant suns had multiple planets with systems similar to our own solar system, then would it be possible to identify additional planets. It was with all these ideas in mind that I began my quest for the exoplanets.

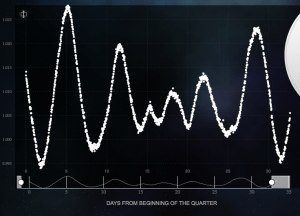

Sometimes, the pattern appeared to be too random to be able to distinguish a planet and at others, beautiful patterns could be seen as if generated by an oscilloscope, these it would seem were possible candidates for a binary star and so these were recorded also. Now and again, a pattern would emerge which would make you sit up and take notice. Using the sliders on the screen, I would drag out the ‘x’ scale to magnify a section of the screen where I was certain a transit was occurring and then I would check to see whether there was a second transit which may indicate its periodicity. It was during such an event that I found, what is recently been called, PH2-b. With, what at time was simply a planetary candidate; I posted a note to see if any of my fellow planet hunters had seen what I had seen.

Carl Sagan spoke of the ‘Pale Blue Dot’, the Earth as seen from Voyager 1 in the distant reaches of space, how exciting would it be if spectral analysis revealed this planet to have water and an atmosphere, another ‘Pale Blue dot’, now that would be truly remarkable.

Hans Martin Schwengeler

I’m a regular user (zoo3hans) on PH, more or less from the beginning two years ago. My name is Hans Martin Schwengeler and I live near Basel in Switzerland. I’m 54 years old, I’m married and we have two children. I’m a mathematician and work as a computer professional. I like to advance Science in general and Astronomy in particular. I did work a few years at the Astronomical Institute of the University of Basel (before it got closed because they decided to save some money…), mainly on Cepheids and the Hubble Constant (together with Prof. G.A. Tammann). Nowadays I’m very interested in exoplanets and spend every free minute on PH.

I’ve always been interested in stars, planets and the universe in general. So when I studied Mathematics at the ETH in Zurich it was natural to choose Astronomy as a second discipline. After working a few years on a Statistics research program (based on the Kalman Filter) I managed to get a job at the Astronomical Institute of the University of Basel (Switzerland) as a system manager. There I could work part time on research programs, mainly on Cepheids to determine the Hubble Constant (together with G.A.Tammann and Allan Sandage). I did this with the image processing software ESO-MIDAS, where we analyzed images taken by the ESO New Technology Telescope (NTT) or the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). I also used a program (written in Fortran-77) called superperiod to find the periods of the variable stars found in the galaxy images and see if they could be cepheids with periods between 2 and 100 days. With the Cepheid period-luminosity relationship we were then able to determine the distance of the Cepheid and the host-galaxy.

As soon as Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz detected the planet around 51 Pegasi, I was drawn in into exoplanets. I followed every single announcement of the detection of a new exoplanet on Exoplanet.eu and arXiv.org and elsewhere. So when I first took notice of the Planet Hunters project, I joined immediately. In the meantime the Astronomical Institute has been closed down (on monetary reasons) and I was working as a systems engineer at the Federal Office for Information Technologies and Telecommunications in Bern. I did not have anymore the tools needed to analyze light curves and so on. I also had to realize that to detect a planet transit in a Kepler light curve is not so easy as I first thought (except for the very big Jupiter-like ones). The learning curve was rather steep. Fortunately some fellow hunters had already gathered some very good insight and also some useful tools. So after some months I think I accumulated enough experience to do some real work here on PH.

So when I got the light curve for KID 12735740 I thought it looks very nice and might be a real planetary transit. Kian Jek had already commented on it favorably. The transit shape is more like an “U” instead of a “V”, the transit depth and duration is compatible with a 1.1 R_Jupiter planet with a period around 282.6 days. We can check this with Kian’s very good Planetary Calculator. The first thing I then usually do, is to have a look at the sky view and then post this image to the PH Talk pages for others to have a look too My second step is then to download the FITS files from MAST (using the very good tools from http://www.kianjin.com/kepler/detrend.tar.gz ), detrend the curve roughly and view it by eye first (often using the program ggobi for this purpose). I upload the light curve also to PH if it looks interesting. Thirdly I may do a periodogram to find the period if a good period seems to be present (and upload it as well of course).

In the case of KID 12735740 I think all looks very good for a real planet candidate. Not much would be possible without the help of others, especially Kian Jek (aka kianjin) is invaluable here at PH. He compiles very good lists of “good candidates” or EB lists. I also find the other lists of “good Q2 candidates (non Kepler favorites)” (or Q3, Q4, etc. lists) very helpful in finding candidates and discuss them in more detail. It’s otherwise rather difficult to keep track of all the interesting cases on PH Talk. Kian does also the best detrending jobs, contamination vector determination, fitting of transit parameters, and more. nighthawk_black does perfect Keppix analysis, troyw has his amazing AKO service, capella, JKD, ajebson, gccgg, Tom128 and many other are very helpful too.So very often we work together here at PH as a good team.

In order to discriminate between real transits and instrumental or processing artifacts, I add comments to the “consolidated list of glitches” in the Science section on the PH Talk site. I collected a few bright and quiet and constant stars over the last few months / years exactly for this purpose. When I see a dip on one light curve and the same feature is also present on the other light curves, then it’s very likely a glitch.

I think the PH project is a great contribution to Science. I’d like to thank all fellow PH hunters for their help and also to Meg.

Kind regards,

Hans Martin Schwengeler (aka zoo3hans)

—

In addition to Mike, Hans, and rafcioo28, several others get a tip of the hat for marking transits in the discovery light curve for PH2: Sean Flanagan, Anand, and Jaroslav Pešek. Congratulations to you as well.

Planet Hunters: An Online Community

The team at Possible including Elena Moffet and Tyler Brain made a short documentary exploring online communities from the perspective of the individuals who compose them. This included talking to people involved with Wikipedia and open source software developers. Our own Katy Maloney reflects on being a citizen scientist and part of the Planet Hunters community. You can watch the final product titled COLLECTIVE: An exploration of online community below:

Revising the PH1 Paper

I just wanted to give you all a quick update on the PH1 paper. We submitted the paper in October to a scientific journal, Astrophysical Journal. We got a few months ago feedback from the referee (another scientist in the field who reads the paper, gives to the editor his/her opinion on if the paper is worthy of publication, and many times raise issues or concerns he/she would like to see addressed before publication will be recommended). Recently, I’ve been working on finishing the response to the referee’s report. I have been making changes and edits to the text to address the specific concerns and questions raised by the referee. I think the changes make it a stronger paper. I sent the revised manuscript to the rest of the coauthors last night. I’m waiting for their comments and feedback. Hopefully in the next few weeks, we’ll have the paper resubmitted to the journal and referee. With any luck, hopefully the paper will be accepted soon after that. I’ll keep you updated on our progress.

Starspots and Transits

There was a great question about transits in response to my post about “What Factors Impact Transit Shape” so I thought I’d answer in a blog post.

Jean Tate asked:

Question: In the image of Venus transiting the Sun, there are sunspots. How common are sunspots on the Sun-like stars in the Kepler field? How do sunspots change the transit light curve? How are sunspots modeled?

Starspots are dark blotches on the surface of the star and are regions of intense magnetic activity. Their temperature are lower than the rest of the photosphere which gives them their dark appearance. These blemishes are transitory and last anywhere from hours to months. They are an indication of the magnetic activity of the star, and the Sun goes through an 11-year cycle where the number of starspots (or sunspots as we call them on the Sun) changes. The more active the Sun, the more sunspots visible on its surface.

If you viewed the transit of Venus last July, there were several sunspots on the surface of the Sun which you can see in the image below.

Transit of Venus – Image credit- Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:2012_Transit_of_Venus_from_SF.jpg – Venus is at the top right of the Sun’s disk. Other dark blotches are sunspots.

On the Sun we can actually spatially resolve the sunspots, but on other stars we can’t. So for Kepler that is monitoring stars thousands of light years away, we detect starspots through the light curve. As the star rotates, starspots will come in and out view causing changes in the star’s brightness. The pattern in the star’s light curve will repeat once per rotation period of the star. At the equator, the Sun rotates every 24.47 days much longer than the short few-tens of hours that a planet transit lasts.

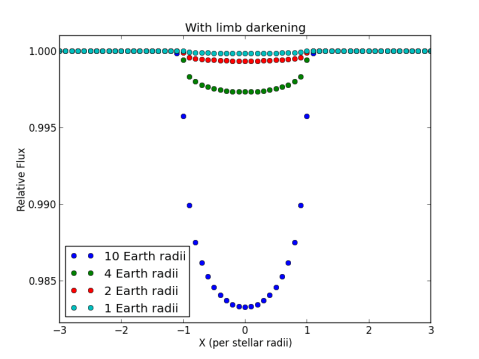

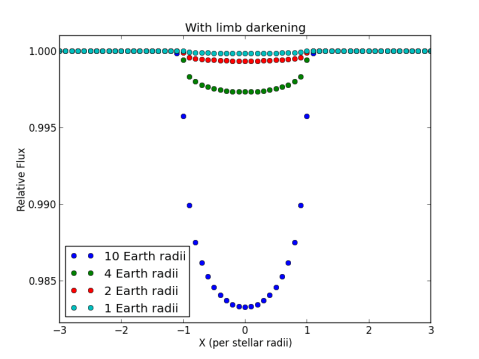

If the transiting planet doesn’t cross over a starspot we get a fairly rounded U-shaped symmetric bottom to the transit as you can see below for a set of simulated planet transits.

Simulated planet transits including limb darkening of the star. For the plot I assume the star 0.8 times the radius of the Sun and the planets cross the center of the star

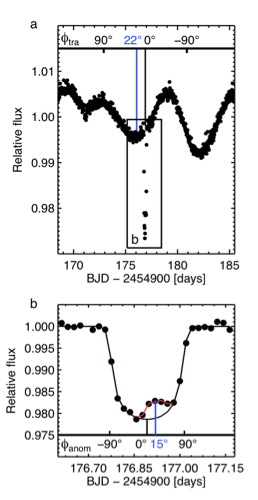

Because planet transits last a few to tens of hours and stars rotate over a period of days, you can think of the starspot as effectively stationary with the planet moving across it during the transit. The starspot is not as bright as the surrounding areas of the photosphere, so when the planet transits across that starspot the lightcurve gets a bit brighter than average and you don’t see a symmetric bottom to your transit. So you see a small positive bump in the transit lightcurve. In the observed transit shown below, the planet crosses a starspot during the second half of the transit.

Planet transit of Kepler-30c across a star spot Figure from Sanchis-Ojeda et al 2012. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.5804)

Planets transiting starspots can be extremely useful. Those transits have been recently used to measure the alignment of the planet’s orbit to the rotation axis of the star. In our Solar System, the planets are about 8 degrees off from being aligned with the Sun’s rotation axis, but other planetary systems are severely misaligned.

If the planetary system is aligned with the star’s rotation axis, then the planet transit path is a chord that always crosses over the starspot when it is in view, so you will see many of the planet transits having the signature of a starspot crossing. Because the star is also rotating between transits, the starspot will be likely be in a different place on the star’s disk the next time the planet comes around so you will see the timing of the bump change from transit to transit. If the orbit is misaligned, then only when the starspot is in a position crossing the planet’s transit chord across the star’s surface will there be a positive bump in the transit lightcurve. So the next several transits the planet has extremely low chances of being timed such that the starspot is in the same position on the star’s disk for the event to repeat. So you should see no starspot signal in subsequent transits. You can see this effect below in the figure from Sanchis-Ojeda et al 2012.

Figure from Sanchis-Ojeda et al 2012 (http://arxiv.org/abs/1211.2002)

What factors impact transit shape

I’m rewriting the simulation code I use for making simulated transits and injecting them into Kepler light curves from a program language called IDL to python. I’m working on a new paper idea and project with Planet Hunters so I thought now would be the perfect to time to make the coding switch. The actual part of the code that computers the shape of the transit comes from publicly available code written by another astronomer, Ian Crossfield (if you want to play with the code you can find it here).

I’ve been doing some simple tests to make sure the code works and thought that it would be worth using the test output as a great way to talk about a few things that affect the transits that you see in the Kepler light curves on the Planet Hunters website.

Ratio of the size of the planet to the size of the star:

The transit depth is the ratio of the surface area of the star’s disk blocked out by the planet’s disk. So the transit depth is the square of the planet radius divided by the star’s radius. The majority of Kepler stars are similar in size to the Sun or a bit bigger or smaller, so in general the bigger the planet the bigger the transit you see.

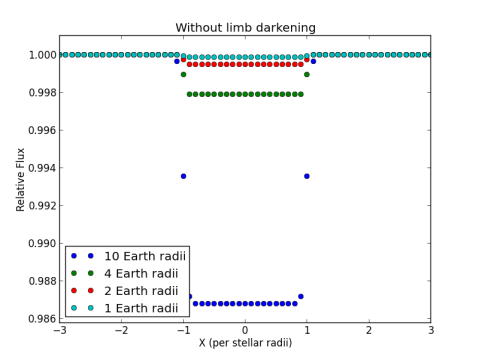

Below is the ideal transits you’d see for a series of planet radii assuming the star was perfectly quiet and is uniformly bright. For the plot below I assume the star 0.8 times the radius of the Sun and the planets cross the center of the star.  These transits are very boxy – In real life they won’t look like this at least not on the ingress and egress (the edges of the transit). That’s because the a star is not a uniformly illuminated disk. It is darker at the edges than it is at the center. We call this limb darkening. What is happening is that you are seeing into different layers of the Sun depending on how far from the center of the disk. So the center is hotter layers and therefore brighter than the edges. You can see the effect when looking at the Sun shown below during the transit of Venus.

These transits are very boxy – In real life they won’t look like this at least not on the ingress and egress (the edges of the transit). That’s because the a star is not a uniformly illuminated disk. It is darker at the edges than it is at the center. We call this limb darkening. What is happening is that you are seeing into different layers of the Sun depending on how far from the center of the disk. So the center is hotter layers and therefore brighter than the edges. You can see the effect when looking at the Sun shown below during the transit of Venus.

Transit of Venus – Image credit- Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:2012_Transit_of_Venus_from_SF.jpg – You can see the limb darkening is quite apparent. The edges of the sun are darker than the center.

Limb darkening changes mostly the edges of the transit making them softer and rounder less box like. If we account for limb darkening for the same planet transits shown in the previous plot, they now look look this:

Simulated planet transits including limb darkening of the star. For the plot I assume the star 0.8 times the radius of the Sun and the planets cross the center of the star

You can see the transits are more U-shaped like we see in the Planet Hunters interface. Now the plot is very zoomed in, it shows 3x the star’s radius on either side, but if you zoomed in on Planet Hunters this is what you’ll see for a spotted transit if the planet is very large and the transit depth is pretty large compared to the measurement noise of Kepler.

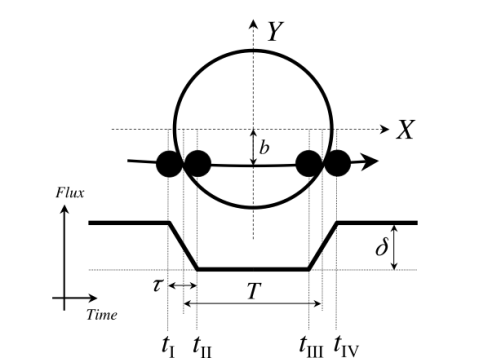

Another factor to account for is the impact parameter. You can think of the planet’s transit across the star in the x- direction and think of the impact parameter as the y project coordinate of the transit. In essence you can think of as the impact parameter (b) as how close in the y direction is planet to the center of the star’s disk.

Transit schematic from Winn 2011 – http://arxiv.org/abs/1001.2010v3

Changing the impact parameter changes the duration of the transit. If we assume no limb darkening and a uniformly illuminated stellar disk this is what you would see:

Larger b higher from the center of the star the planet crosses. Transits of a 10 Earth radii (Jupiter-sized planet) with varying impact parameters and no limb darkening assuming a 0.8 x Solar radius star

Now if we add in limb darkening we get:

Larger b higher from the center of the star the planet crosses. Transits of a 10 Earth radii (Jupiter-sized planet) with varying impact parameters with limb darkening assuming a 0.8 x Solar radius star

You can see for the highest impact parameter (where the planet is crossing very close to the edge of the star) the transit looks pretty V-shaped like an eclipsing binary eclipse when we account for limb darkening. This is why if you see a V-shaped transit we typically think it’s most likely not a planet transit because the vast majority of times the planet transits will be U-shaped with a flatish bottom. You also see the depths on the bottom change slightly. This is because they are not all crossing the very center of the star which is the brightest point anymore.

One other factor that will effect the shape will be the duration of the transit which depends on the orbital period of the planet and the eccentricity of the orbit, but for all of these plots I’m plotting in the X-axis in terms of the size of the star.

New Features on the Source Pages and Other Updates

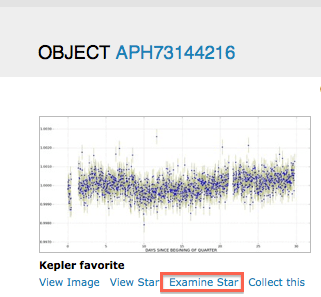

With the Kepler extended mission in full swing, we have added some new data to the source pages to help your investigations. If you don’t know what a source page is, it’s where we show all the light curve data for a given Kepler target that we have uploaded on the Planet Hunters website as you would see it in the main classification interface. We show roughly 30 day light curve segments in the main Planet Hunters classification interface, so on the source pages you can peruse the other light curve sections. In addition the source page is the place where you can get the Kepler ID of your favorite star and look up other information about the Kepler source.

You can get to the source pages by clicking on the “Examine Star” link (see below) on any Talk light curve page.

The source pages now include some new links to reflect some of the new data on Kepler stars now available. At the top of each source page you’ll see several links: Add to Favorites – Download Data – Kepler Archive – Kepler TPS – UKIRT DB

Download Data: The Download Data link will download to your harddrive a csv file of all the light curve data we have uploaded for that star.

Kepler Archive: The Kepler Archive link will take you to a Kepler Catalog Search which outputs the Kepler id of the star, it’s position on the sky (right ascension and declination), magnitude, colors, etc.

***New Features***

The Kepler TPS: In the Kepler Extended Mission, the Kepler team is now releasing their list of Transit Crossing Events (TCEs) from their main Transiting Planet Search (TPS) code. A TCE from TPS is not a planet candidate. It’s a possible series of linked transits, identified by TPS that has hit the criteria for being considered a detection. There’s a lot of work needed to go from TCE to planet candidate. TPS detects may thousands upon thousands of TCEs and most of these are false positives. So lots of other checks have to be made to validate the possible transit detection to a planet candidate. For the Quarter 1-12 run of TPS there are over 18,000 TCEs. The TCE list has not been vetted by the Kepler team. Probably only a few thousand are actually real. Provided by the Kepler team is the data validation report for each TCE. This is the output from their data validation pipeline of some tests to assess whether the TCE may be a real planet candidate. (You can learn more about the TCEs and other data products provided in the Kepler Extended Mission here.) The Kepler TCE link will search the TCE list and report back if there was a hit on the TCE list with some info about the properties of the detection, which you can then further investigate on the NExSci website. If there are columns names and nothing else when you click the Kepler TPS link that means the source is not on the TCE list.

UKIRT DB Link: The Kepler pixels are rather large. Each pixel in a Kepler image is 4 arcseconds. The typical photometric aperture radius for a Kepler target star is 6 arcseconds, and all the photons collected by the CCD within that radius are assumed to come from the target star and summed to make the Kepler light curve you see. With such a wide aperture, stellar contamination and photometric blends are a concern. Adding linearly, the contribution of extra light decreases from other stars within the Kepler aperture causes the observed transit depths to be shallower than they really are. Accurately estimating the size of the transiting planet requires knowledge of the additional stars contributing to the Kepler light curve to correct for this effect. Also knowing there are additional stars in the Kepler photometric aperture is important because it can help identify that a Kepler source;s light curve is being contaminating by a nearby star that is an eclipsing binary. By clicking on the UKIRT DB link, you get a search reporting back UKIRT J band (near infrared) images of the Kepler star from the WFCAM Science Archive. The typical pixel scale is 0.8-0.9 arcseconds per pixel, which allows us to zoom in within a few arcseconds of the Kepler target. (Thanks to Mike Read from the WFCAM Science Archive for helping set this up and to Phil Lucas for generously letting us link to the data in this way).

—-

Other updates to the site include updating the lists of known eclipsing binaries, false positives, and Kepler planet candidates. The Kepler team last week released their list of planet candidates and false positives from analysis and vetting using data from Q1-Q8. The Talk labels have been updated to reflect this. The eclipsing binary list comes from the July 2012, since that’s the last static list to be released.

AAS Meeting in Long Beach California

Tomorrow I’m heading to sunny southern California. I’m heading to the American Astronomical Society’s (AAS) 221st meeting in Long Beach, California. Right before the meeting in Long Beach on January 5th and 6th, I will also be attending the National Science Foundation’s Astronomy & Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellows Symposium. At both I’ll be talking about Planet Hunters. Also Stuart Lynn from the Adler Planetarium and the Zooniverse development team, one of the chief architects behind Planet Hunters, is going to be at the NSF symposium as well. Stuart’s going to be participating in the Novel Approaches to Public Outreach panel. I’m sure he’ll be talking all things Planet Hunters and Zooniverse at the symposium. Science team member Kevin Schawinski will also be attending the AAS meeting as well.

I’m giving my AAS talk on January 9th in the morning exoplanet session. My title is Planet Hunters in the Kepler Extended Mission. I’ll be talking about the discovery of PH1 and where the project is moving in the Kepler extended mission in addition to presenting some of new preliminary results from the science team. If you’re on twitter you can follow the conference live. Many of the astronomers attending (including me) will be using #AAS221 and for the NSF Symposium we’ll be using #AAPF13