A Newly Spotted RR Lyrae Star

Although Kepler was designed to find extrasolar planets, the Kepler light curves with their high temporal cadence and measurement precision is a rich data set for studying stellar astrophysics. Although the main goal of Planet Hunters is to search for new extrasolar planets, the Talk discussion tool was designed to enable volunteers to be able to identify other types of potentially interesting variable stars and oddball light curves that we weren’t necessarily looking for with the main classification interface.

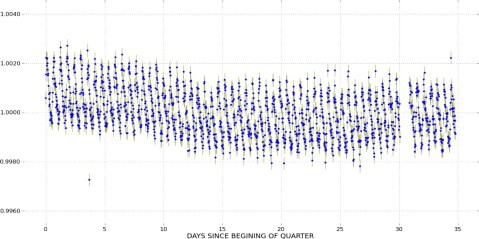

With so many eyes looking through the light curves for 160,000 stars on the website, we’re bound to find an interesting star or two, and we have. Planet Hunters has helped discover a new RR Lyrae variable star. This is the second one spotted by Planet Hunters. Just like the first (which was spotted a year ago), this one was spotted by the keen eyes of our volunteers on Talk. It was reported to the Science Team, and Chris contacted the Kepler folks who study these sorts of thing, and it looks like it is indeed a new find. Congratulations to all involved. The RR Lyrae discovery is actually not the Kepler target star, but is nearby and contributing light into the photometric aperture, contaminating the actual Kepler star’s light curve with it’s changing brightness.

RR Lyrae’s are a special type of variable star. The radial pulsations cause the star to expand and contract producing observed changes in the star’s luminosity and subsequently the observed light curve. The American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) has a nice writeup describing the history and properties of RR Lyraes. Because the pulsations are supposedly simple radial expansion, these stars are often used as standard candles for measuring distances. But there is still a lot to learn about these stars. In particular, the underlying cause of Blazhko modulation, a periodic amplitude and/or phase variation of the pulsations with a period of typically 10-100x the typical pulsation period, that some of the RR Lyraes undergo is still an open question in stellar astrophysics.

This class of variable stars is named for the prototype star, RR Lyrae, first identified to exhibit these oscillations and observed patterns of variation. The original RR Lyrae just so happens to be in the Kepler field as KIC 7198959. There are currently about 40 known RR Lyrae stars in the Kepler field, so this is indeed a rare find. This new find will subsequently be studied by the Kepler Cepheid & RR Lyrae Working Group, and hopefully eventually be included in publication featuring all RR Lyrae stars identified in the Kepler field.

Frequently Asked Questions

We’ve had many new people join Planet Hunters over the past several months (Welcome to all of you), and I thought it would be good to spend a blog post answering some of the recurring questions that get asked on the forums that our Talk moderators, the science team, and other members of the Planet Hunters community have answered in one spot for both new and veteran volunteers.

Q: How many people look at each light curve?

A: Currently 5 people review the same 30-day light curve. We combine the results from all the classifications of that light curve to make an assessment to decide if there is a transit or not. This is known as the wisdom of the crowd. By combining the results of many non-experts you can match or outperform an expert classification. You can read more about how we do that for Planet Hunters here. Once there are 5 classifications the light curve it is retired and a new unclassified light curve makes the list. We do have some preferences for what light curves get shown, but it’s roughly a random draw with a few rules. Those rules prioritize the light curves so that for example we show new light curves that don’t have known planets more than showing Kepler favorites or known eclipsing binaries to optimize changes of discovering something new.

Q: Is it possible go back and reclassify a light curve I’ve already classified?

A: No, once the classification has been submitted you can’t go back and change it. It’s okay if you’ve missed something or made a mistake. Usually if you see something other people who classified a light curve will as well and will have marked it.

Q: I just started with Planet Hunters. Am I starting from the beginning and seeing old data that’s already been classified by previous classifiers months ago?

A: You’re seeing the newest data we have on the website. Though we are currently showing data that has already been searched for planet transits by the Kepler team’s automated routines, we think there may be transits that the computer algorithms may have missed. Starting in 2013, the Kepler light curves will be released publicly at the same time as the Kepler team gets to see it, and we’ll be uploading that data as fast as we can go through classifying Quarters on the Planet Hunters website.

Q. What’s a Kepler favorite, and why doesn’t it show up under My Candidates?

A. A Kepler favorite is a star the Kepler team thinks has planets of its own and have identified what they believe to be planet transits. We don’t list those on your planet candidates list. We only list things Planet Hunters has identified as new planet candidates.

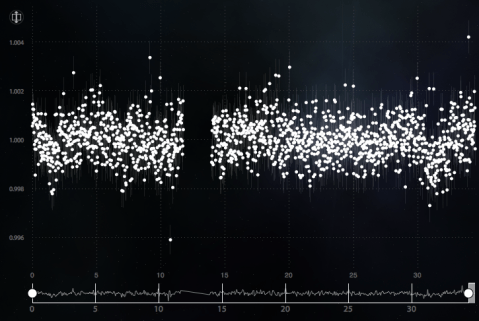

Q. What’s an eclipsing binary (or what’s an EB)?

A. An eclipsing binary or EB is a pair of stars that are gravitationally bound to each other and orbiting their common center of mass,. We call this an eclipsing binary because the smaller star passes behind and in front of the larger star along our line of sight. When the smaller and cooler of the two stars transits in front of the larger hotter star you get a drop in light like with a planet . We call this drop in light a primary eclipse. The difference from a transiting planet is that a planet has no significant light in the optical compared to a star, so when it passes behind you typically don’t see anything observable in the optical. In this case we have two stars that are luminous so we loose the light of the second star when it passes behind the larger star. That produces a smaller drop in light we call a secondary eclipse. So for a eclipsing binary light curve you get a big dip small dip repeating pattern. The light curve looks something like this if the stars are well separated:

You can learn more about eclipsing binaries in these blog posts (here and here)

Q. I can only mark 18 transits before the Finish button goes away. What do I do?

A. This is a known bug in the interface. We won’t be fixing that in this version of the site. Just mark as many as you can before the Finish button goes away (that should be about 18).

Q. How do you want me to mark EBs in the classification interface?

A. Mark the primary and secondary eclipses or as many as you can before the submit button goes away. The science team will sort out if those are planet transits or stellar eclipses in the light curve.

Q. What if I discovered a planet, will you let me know?

A. Yes, if you were the first to identify a candidate that we can confirm is a planet or the science team writes a paper where the majority of it is devoted to a specific candidate we will ask you to be a co-author on the paper. The Zooniverse has your contact info from when you signed-up. So not to worry we’ll email you. Also since we can’t stick 200,000 co-authors on a paper, every we paper write references our authors page to acknowledge the contributions from all our volunteers who make the science possible.

Q. What are those gaps in the light curve? Is that a big planet transiting?

A. If you see gaps like the ones shown above, that’s not from a really big planet or star that blocks out all of the light from the Kepler target star. It just means that Kepler isn’t collecting data. Usually that’s because Kepler is pointed away from the Kepler field so it can aim it’s antenna towards Earth to send its observations back to NASA. The other reason there might not be data is because something has happen on Kepler and it has entered safe mode to protect itself. When that happens the spacecraft isn’t taking data.

Q. What is the difference between SPH number and APH number?

A. Kepler is monitoring about 160,000 stars. We have chosen to show sections of the light curve that are the same size as the first quarter (35 days), and therefore Quarter 2+ light curves are broken into three sections of roughly 30 days (each quarter is typically 90 days except for Quarter 1). We have 5 days worth of overlap in each section, so that we don’t miss any transits that happen at the starts and ends of where we separated the light curves. You can tell which part of the light curve you are looking at by the APH#. The first two numbers are quarter and section. For example, APH22332480 is section 2 of Quarter 2. Quarter 1 light curves start with APH10. We use APH for the light curve sections and SPH for referring to the star itself. For the SPH numbers the first two numbers refer to what quarter the star first appeared in the public data set. For example, SPH21332480 first appeared is Quarter 2 Section 1. The star source pages (like http://www.planethunters.org/sources/SPH10129795) contain all the sections of light curve (we have available on the site) for you to review and the x-axis is the days from the first observation, so you can look for repeat transits in other sections of the light curve easily. Also available on the source page is a downloadable CSV file which contains all the available light curve data we have on the site.

If you have other questions, check out our FAQ site or Site Guide. If you don’t see the answer you’re looking for, do ask your question on our Talk website

Happy Holidays

Image Credit: Steve Harris (swh) from Flickr http://www.flickr.com/photos/steveharris/5255090489/

Happy Holidays and Merry Northern Winter (and Southern Summer) Solstice from everyone on the Planets Hunters team.

In spirit of the holiday season, each day this month, the Zooniverse has revealed a new gift on the Zooniverse Advent Calendar. Two years ago, Planet Hunters was hiding behind one of the doors. This year there were several Planet Hunters themed surprises (including the background for the Advent Calendar which might look very familiar) :

In case you missed them:

Day 1: Zooniverse Publications Page – Including 3 Journal published/accepted Planet Hunters papers

Day 12: A Live Chat with members of the Science Team

Day 16: Planet Hunters Anniversary Poster composed of all of our volunteers names (can you find yours?)

And be sure to check out tomorrow as the last door opens on the Advent Calendar.

Wishing you a very Happy Holiday,Merry Solstice, and Happy New Year from us to you.

The Planet Characterizer

Today we have a guest post from Seth Redfield. Seth is an Assistant Professor at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT. Before Wesleyan, he was a postdoc in Austin, TX, and a graduate student in Boulder, CO. He is an avid hiker, and an oboe player (with a degree from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston), but these days spends any free time with his kids (4 and 1 years old) and sleeping.

To date, I have working on studying known exoplanets rather than finding them. Instead of a “planet hunter”, you could call me a “planet characterizer” (which doesn’t have quite the same ring to it). Perhaps the most well-studied planet, and one of my personal favorites, is HD189733b. This is because it is a transiting exoplanet, orbiting one of the brightest stars that we know has a planet. The fact that it transits, allows us to use spectroscopy of the starlight from HD189733 while the planet is transiting to look for wavelength-dependent effects that reveal interesting properties of the planet. For example, we can measure the composition, temperature, and even wind speeds in the atmosphere of the planet. The fact that HD189733b orbits a bright star, makes all these measurements “easier”, meaning that they are still incredibly difficult and require careful observations using the world’s largest and most sophisticated telescopes, but nonetheless are possible.

Because transiting planets are so useful, I follow with excitement all the searches of transiting planets, hoping they will find one around a bright, nearby star. However, the strategy for searching is directly at odds with finding one around a bright star. In order to find the rare planetary system that is edge-on, and therefore transits, one must observe many tens of thousands of stars. Bright stars tend to wash out large sections of our detectors and make it difficult to see the multitude of fainter stars around them. For this reason, all the searches largely avoid the bright stars.

Indeed, HD189733b was not discovered first by its transit, but by the radial velocity method of observing the host star orbit the center of mass of the system. It is for this reason, that I feel that the planets that will become household names, meaning the planets whose names will be known by school kids around the world, have yet to be discovered. These will be small, Earth-like planets, for which we can just barely detect using the radial velocity method, but which will also transit a bright host star and thereby make it possible for us to probe the characteristics of the planetary atmosphere.

So, as this young field of exoplanet research matures, I see this clear synergy between the detection of exoplanets and characterization of those exoplanets. Obviously, exoplanets must be detected in order to be characterized. The handful of exoplanet atmosphere detections to-date have uncovered a diverse collection of atmospheres that appear to be influenced by a myriad of planetary and stellar phenomena (such as planetary composition, stellar flares, etc). So, the characterization of exoplanets motivates us to find more exoplanets with new and extreme properties. I feel like we are at a similar point to astronomers 150 years ago when spectroscopic observations of stars were being made for the first time. Every discovered exoplanet is amazing, but it is likely that the planets we are talking about now will not be the planets we will be obsessing over in twenty years.

One final note, is that the brightest stars being observed by Kepler are almost as bright as HD189733, so let me take this opportunity to make a plug for searching the brightest stars in the Kepler field. Anything found to be transiting those stars will certainly be of interest to the “planet characterizers” out there.

New Publications Page

With the start of December, it’s that time of year again. The Zooniverse Advent Calendar is back. Each day this month, a door opens and there’s a new surprise. Planet Hunters was behind one of those doors two years ago. On Day 1, the door revealed the new Zooniverse publications page. There you will find all of the peer-reviewed and Journal accepted papers for Planet Hunters as well as the other projects that make up the Zooniverse. It’s been a busy year with our first paper which was accepted for publication in 2011 officially printed in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 2012, 2 more papers accepted (Schwamb et al. 2012 accepted and published in Astrophysical Journal; Lintott et al 2012 accepted to Astronomical Journal), and the PH1 paper submitted. You’ll see the PH1 paper isn’t listed there yet. That’s because it’s still in the peer-review process. We’re the midst of responding to the referee’s report and resubmitting the paper to the Journal and the referee. We hope to have it accepted and listed there on the Publications page soon.

P.S. Thanks for all of your hard work to help make these publications happen. We can’t add thousands of names to the paper authorship, but we acknowledge your time, effort, and contribution to all of our publications on our authors page .We update the authors page each time a paper is accepted for publication. The link to the authors page is in the acknowledgements of every Planet Hunters paper.

P.P.S. The background image for the Zooniverse Advent Calendar might look very familiar.

Keck Observing Scheduled for Next June

The Keck Observatory observing schedule was released online over the weekend. It’s released twice a year around June 1st and December 1st listing the exact dates those astronomers who have been awarded with telescope time will have on the 10-m Keck telescopes located on Mauna Kea. I was awarded one night by the Yale Time Allocation Committee (TAC) with the NIRC2 instrument and Natural Guide Star Adaptive Optics to zoom in around Planet Hunters’ planet candidate host stars and look for contaminating stars that may be contributing light to the Kepler light curve. This will allow us to better assess the planet radius and the false positive likelihood for those candidates. To learn more about NIRC2 and Natural Guide Star Adaptive Optics, check out a previous guest blog by Justin Crepp.

Our observing night on Keck II has been scheduled for June 28, 2013. The Kepler field (in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra and part of the Summer Triangle), will be high in the sky for most of the night and easily observable from Hawaii. Below, I’ve plotted the airmass (Y axis scale on the left ) and altitude (Y axis scale on the right) of the Kepler field for our scheduled night. Except for about an hour at the beginning of the night, the Kepler field will be above 30 degrees altitude and easily observable from Keck for the duration of the night.

Part of the science team will be heading out to Keck Headquarters on the Big Island of Hawaii to observe. Let’s hope the night is clear. If it rains or is really cloudy, we’ll be out of luck. The rest of the nights on Keck II are scheduled for other observing projects and assigned to other astronomers. We would then have to try again next year and reapply to the Yale TAC for the telescope time. I’m hoping (fingers crossed) that the weather will cooperate and that we end up with lots of useful data.

We won’t be going up to the summit of Mauna Kea (at 14,000 feet!) where the telescope is located on June 28th. A telescope operator will be run the telescope from up at 14,000 feet. We’ll remote observe from sea level at Keck Headquarters (shown below) in Waimea, Hawaii where we won’t have to worry about the effects of being at high altitude.

The operator will drive and control the telescope and the adaptive optics equipment. We as the night’s observers will control the camera and run the show determining where we want to point on the sky and in what order. We’ll plan and think more about the run next year in June closer to when we fly out to Hawaii. We’ll make sure to blog, tweet, live chat and keep you all up to date on how the night and the observing goes.

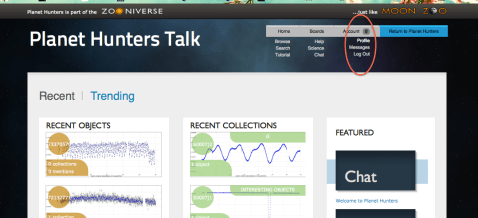

Some New Features in Planet Hunters Talk

We’ve added some new features to Planet Hunters Talk in the early Fall that you might not be aware of. For our new volunteers, Talk is our forum/discussion tool where you can share your thoughts about light curves you’ve classified and interact with other members of the Planet Hunters community.

If you haven’t been to Talk before you can get to the site in two ways – one by directly going to http://talk.planethunters.org/ or when you’re classifying a lightcurve and answer “yes” to “Would you like to discuss this star?”. When you answer “yes”, you are brought to the dedicated page for that specific light curve you classified on Talk where you can write a 140 character comment, add a twitter-like hashtag, or start a side discussion. Talk also allows you to collect similar light curves together in collections.If you’re new to Talk or just want a refresher, we’ve added a brief tutorial which you can find here.

I wanted to share some of the new features that have been added a few months ago that you might not be taking advantage of. One of our new features is emoticons 🙂 . The other is “Watched Discussions.” For any discussion on talk you want to stay up to date on, you can now receive emails when there is a new response posted including the text from the posted message.

For all discussions on Talk below the title you’ll see a link labeled “watch discussion.” By clicking that link the thread will be automatically added to your account’s “watched discussion” list, and you will immediately start receiving emails when there is a new post. This feature exists both for the message boards and for side discussions about specific light curves/stars.

You can find out what discussions you are watching and will receive emails for by going to your profile page. From there you can also change your preferences and remove or modify the list. If you move your mouse over the Account button on the top right of the Talk website, you’ll get a menu that includes the link to your account profile. Click on “Profile’ and from there you can change your preferences and the discussions you are following

Once you’re on your profile page – you’ll see options to enable/disable receiving email as well as the ability to remove Talk threads from your Watched Discussions” list.

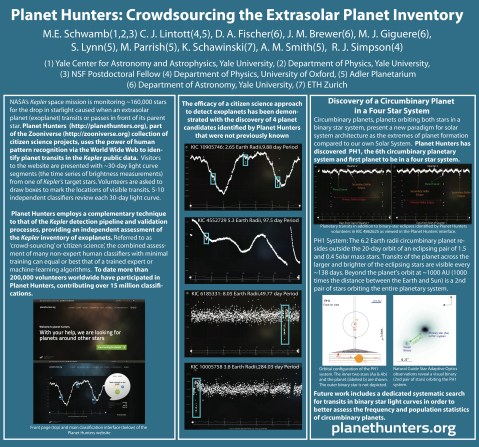

Poster for the Kavli Frontiers of Science Japanese-American Symposium

I’m attending the Kavli Frontiers of Science 13th Japanese-American Symposium in Irvine, California this weekend. I’m going to present a poster on Planet Hunters to a mix of scientists from all different backgrounds. I thought I’d share the poster I’ll be bringing with me showing the current highlights from the project.

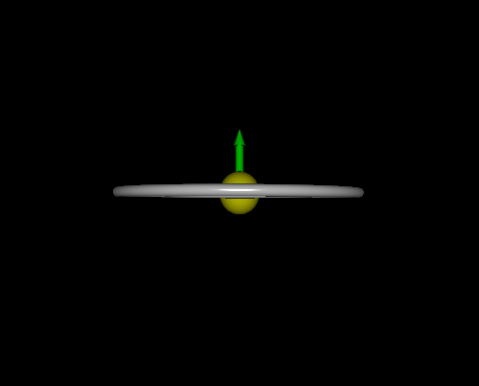

Turning Planetary Systems on Their Heads (Gently)

Today we have a guest post from Nate Kaib. Nate is a postdoctoral researcher at Northwestern University. In terms of research, his main interests lie in using computers to model the orbital dynamics of exoplanets as well as the small bodies of the solar system. He’s written numerous papers on the evolution of comet orbits within our own solar system and how they can be used as a tool to constrain the solar system’s history. More recently Nate has gotten interested in the evolution of planetary systems residing in binary star systems.

In a select number of exoplanet systems, astronomers have successfully measured the inclinations between the stellar equators of parent stars and the orbital planes of the planets found around these stars. This is done by measuring something called the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect, which is a subtle change in the Doppler shift of a star’s light that occurs during a planetary transit (see wikipedia for a brief overview). Based on models of star and planetary system formation we would expect all of these inclinations to be near zero since the star and planetary system form out of the same spinning, collapsing gas cloud. Indeed, our Sun is only inclined about 7 degrees with respect to the Earth’s orbit.

Surprisingly, however, groups led by Amaury Triaud and Josh Winn have found that many planet orbits are highly inclined to the equators of their host stars. In fact, some are even retrograde, meaning the planet orbits the star in the opposite direction that the star spins. Explaining these results has presented a major problem for theorists, but several promising mechanisms have been proposed. Most of them assume that all planetary systems initially form with the star’s spin and planetary orbits aligned. However, later dynamical processes alter the planetary orbits. These include planets scattering off one another during orbital instabilities as well as Kozai resonances, which is where a distant massive perturber such as a giant planet or binary star excites both the inclination and eccentricity of an inner planet.

These previously proposed mechanisms imply that highly inclined planet have all gone through at least one major disruptive instability. This would then seem to preclude well-ordered multi-planet systems similar to our own solar system from having planetary orbits that are highly inclined with respect to their star’s equator. In a recent paper, however, we showed that an additional mechanism exists to alter planetary orbital inclinations, rigid body precession. Unlike the other mechanisms, this one will only act in well-ordered tightly packed systems of multiple planets (like our own). The other key ingredient is that there must also be a distant binary star in the system. In this configuration, the binary star’s gravity tugs slightly on the planetary system. These perturbations are very weak but add up over time. If only one planet is present in the system, then the Kozai resonance mentioned above will usually be activated. However, if more than one planet is present, then the self-gravity of the planets cause them to evolve in a coherent manner. They remain on nearly circular orbits, and their mutual inclinations all remain low. Instead, the plane of the entire planetary system begins to tip over relative to the star. (How far it tips over depends on the exact orbit of the binary star.)

As a proof-of-concept, we demonstrated in a recent paper that such rigid body precession is likely ongoing in one very well-known planetary system, 55 Cancri. This system consists of 5 planets on roughly circular orbits. In addition, there is a small star orbiting the entire system at 1000 AU. Because this star takes at least 10000 years to make one orbit, we do not know its true orbit. To characterize its potential effect, we therefore ran hundreds of computer simulations modelling its effects on the planets for many different plausible binary orbits. The final results indicate that the star causes this rigid body precession most of the time, and we found that the most likely angle between the planet orbits now and their original plane is a little over 60 degrees. Thus, in addition to flipping over planetary orbits by more violent processes, it may be possible to do it gently and wind up with planetary systems like our own that are highly inclined to their host star.

To better understand rigid body precession, below is a movie (click on the image to view the movie) made from one of our simulations. In this movie, the white orbits are the two outermost planets of 55 Cancri. (The binary star is not shown since it is 200 times further away.) The green arrow marks the initial orientation of the planetary orbits, while the red arrows marks the instantaneous orientation. This evolution shown in this particular movie takes place over 50 million years, but other simulations require billions of years for similar types of evolution to occur (depending on the exact binary orbit).

Awarded Telescope Time on the Keck Telescope

To study and follow-up planet candidates we find with Planet Hunters we need telescope time. Nights on telescopes are precious and astronomers apply twice or more a year asking for the telescope time they need for their proposed research projects.Yale University has access to ~16-20 nights a year on the Keck telescopes in Hawaii. In September, I applied for telescope time to get a night on Keck II in order to zoom in around the host stars of our planet candidates and see if there are other stars that are contributing light to the measured Kepler light curve.

In an ideal case the depth of the transit is equal to the squared ratio of the radius of the planet to the star’s radius. But if there is any additional light from a neighboring star in the photometric aperture this will dilute the transit making it shallower. Without knowledge of the contaminating stars, one is unable to accurately assess the planet properties, and will wrongly estimate a smaller radius for the planet. Kepler has relatively large pixels (with a pixel scale of 4” per pixel) and a typical 6” radius photometric aperture used to generate the Kepler light curves. This means that there could be stars contributing starlight to the Kepler light curve making the transit shallower.

Using Natural Guide Star (NGS) Adaptive Optics (AO) imaging with NIRC2 on the Keck II telescope, we can achieve 10 miliacrsecond per pixel resolution revealing close companions within 5” of the planet candidate host star.We’ve used AO observations in the past to study PH1. Those observations were crucial revealing the second pair of stars orbiting outside the orbit of the planet. Also those observations helped us get the correct parameters for the size of PH1.The AO imaging basically lets us remove some of the blurriness in the star that we see in our images caused by turbulence in the Earth’s upper atmosphere (this is what causes stars to twinkle when you look at the night sky). The AO system helps morph the telecope mirrors in real time to correct for the changing upper atmosphere and get the resolution to see what other stars share the Kepler photometric aperture summed up to make the Kepler light curves you review on the Planet Hunters website.

There’s good news. The Yale Time Allocation Committee (TAC) awarded us one night some time in June or July next year with NIRC2 for my proposal. Around December 1st, we’ll find out about the Keck telescope schedule and know exactly what night we’ll get to observe on Keck II. Since no one on the team has used the NIRC2 instrument before, we cannot remote observe from Yale, so some of the team will be heading to the Big Island in Hawaii. We won’t be observing from the summit of Mauna Kea (at 14,000 feet) . We’ll remote observe from sea level at Keck Headquarters in Waimea, Hawaii.

Aloha,

~Meg