Quarter 14 Data

Thanks to everyone’s efforts we’ve nearly completed all of Quarter 7 data. Last week, Quarter 14 was uploaded and went live on the site. Quarter 14 is the most recent Kepler observations to be released by NASA during Kepler’s extended mission. It covers observations spanning June 28th – October 3rd 2012 (the last full Quarter during the primary mission).Quarter 14 was processed and made available on the MAST (Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes) public archive in early February. With Q7 mostly done, we decided to jump ahead and show the data as close to off the telescope as we could get!

As with any new Quarter, there are now new opportunities to find previously unknown planets. Quarter 14 was released to both the Kepler team and to the public at the same time in February. Quarter 14 has yet to fully analyzed by the Kepler team. The Kepler team has released their list of potential transit detections from Quarters 1-12 in December and list of planet candidates from Quarters 1-8 in January. So there may very likely be never before seen transits found in Q14.

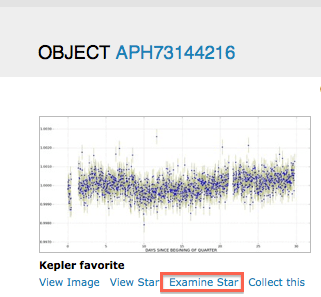

You might have also noticed a change in the naming of the light curves, and that the APH ids now significantly differ from the SPH ID. We basically ran out of namespace to do the SPH-APH mapping well, so we’ve switched over to this new naming system. You can tell what SPH star and Kepler ID correspond to the light curve you are looking at by going to the Talk page for the light curve and clicking on Examine Star (that will take you to the source page). The APH ids still can tell you what quarter of Kepler data you’re looking at. The quarter identifier comes right after “APH” . Before Q14, it was a number (1-7). Now for Q14, we are using “E” to denote 14. The next number following the quarter identifier, still tells you which chunk of Q14 you’re looking at.

Making Way for Q13 Data

The Kepler field will be high in the sky starting in the next month or so and continuing over the Summer months. Thanks to all of your hard work and classifications, the science team has been writing observing proposals to ask for telescope time on the the Keck telescopes in Hawaii to follow up on our best planet candidates. We’ll learn in a few months whether we have been granted the nights. So stay tuned!

In the meantime, the team is continuing to search for new planet candidates with your classifications and Talk comments. You have been analyzing light curves from Quarter 7 released by NASA during Kepler’s primary mission. To begin searching the first data release of Kepler’s extended mission, Quarter 13, we need to finish Quarter 7. We need your help to make room for the new light curves.

As with any new data, there are now new chances to find even more planets. Let’s make the final push so that by April we could be looking at Q13 data. Please get clicking today at http://planethunters.org

Happy Hunting,

~Meg

A slightly unusual look at PH1

One of the many varied things I get to do with my time is act as an advisor to the Oxford Sparks project. As part of our mission to inform the world about the wonderful science this place is involved in, we get to produce animations like this :

The eagle-eyed will have spotted that there’s a world in there familiar to Planet Hunters volunteers, as our slightly intrepid hero is whizzed past PH1. There’s another interesting link, I think, between the two projects; both planet hunters and the animation take us to the cutting (some would say bleeding edge) of science.

Pretty much everything in the animation is open to question (and you can read more background over on the main Sparks site) – we have only weak evidence that there was a fifth giant planet in the Solar System, and many question the portrayal of the sudden bombardment of the Moon as shown here – it’s difficult to tell whether the evidence we have points to a true sudden bombardment or the mere end of a longer period of increased impact probability. On the broader questions too, there is disagreement – what sort of world would really be suitable for life? Do Earth-like planets such as the one we end up with really exist out there? (Probably – but we’re not sure yet).

All of this is ok. My aim – our aim – was to present science with the ink still wet rather than wait for the final draft. After all, it’s most inspiring when we can still make discoveries, and hopefully the video will make people think – and maybe even make a few discoveries of their own on Planet Hunters.

Chris

Planet Hunters: An Online Community

The team at Possible including Elena Moffet and Tyler Brain made a short documentary exploring online communities from the perspective of the individuals who compose them. This included talking to people involved with Wikipedia and open source software developers. Our own Katy Maloney reflects on being a citizen scientist and part of the Planet Hunters community. You can watch the final product titled COLLECTIVE: An exploration of online community below:

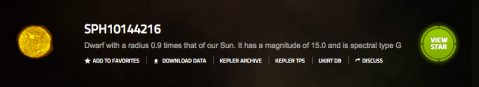

New Features on the Source Pages and Other Updates

With the Kepler extended mission in full swing, we have added some new data to the source pages to help your investigations. If you don’t know what a source page is, it’s where we show all the light curve data for a given Kepler target that we have uploaded on the Planet Hunters website as you would see it in the main classification interface. We show roughly 30 day light curve segments in the main Planet Hunters classification interface, so on the source pages you can peruse the other light curve sections. In addition the source page is the place where you can get the Kepler ID of your favorite star and look up other information about the Kepler source.

You can get to the source pages by clicking on the “Examine Star” link (see below) on any Talk light curve page.

The source pages now include some new links to reflect some of the new data on Kepler stars now available. At the top of each source page you’ll see several links: Add to Favorites – Download Data – Kepler Archive – Kepler TPS – UKIRT DB

Download Data: The Download Data link will download to your harddrive a csv file of all the light curve data we have uploaded for that star.

Kepler Archive: The Kepler Archive link will take you to a Kepler Catalog Search which outputs the Kepler id of the star, it’s position on the sky (right ascension and declination), magnitude, colors, etc.

***New Features***

The Kepler TPS: In the Kepler Extended Mission, the Kepler team is now releasing their list of Transit Crossing Events (TCEs) from their main Transiting Planet Search (TPS) code. A TCE from TPS is not a planet candidate. It’s a possible series of linked transits, identified by TPS that has hit the criteria for being considered a detection. There’s a lot of work needed to go from TCE to planet candidate. TPS detects may thousands upon thousands of TCEs and most of these are false positives. So lots of other checks have to be made to validate the possible transit detection to a planet candidate. For the Quarter 1-12 run of TPS there are over 18,000 TCEs. The TCE list has not been vetted by the Kepler team. Probably only a few thousand are actually real. Provided by the Kepler team is the data validation report for each TCE. This is the output from their data validation pipeline of some tests to assess whether the TCE may be a real planet candidate. (You can learn more about the TCEs and other data products provided in the Kepler Extended Mission here.) The Kepler TCE link will search the TCE list and report back if there was a hit on the TCE list with some info about the properties of the detection, which you can then further investigate on the NExSci website. If there are columns names and nothing else when you click the Kepler TPS link that means the source is not on the TCE list.

UKIRT DB Link: The Kepler pixels are rather large. Each pixel in a Kepler image is 4 arcseconds. The typical photometric aperture radius for a Kepler target star is 6 arcseconds, and all the photons collected by the CCD within that radius are assumed to come from the target star and summed to make the Kepler light curve you see. With such a wide aperture, stellar contamination and photometric blends are a concern. Adding linearly, the contribution of extra light decreases from other stars within the Kepler aperture causes the observed transit depths to be shallower than they really are. Accurately estimating the size of the transiting planet requires knowledge of the additional stars contributing to the Kepler light curve to correct for this effect. Also knowing there are additional stars in the Kepler photometric aperture is important because it can help identify that a Kepler source;s light curve is being contaminating by a nearby star that is an eclipsing binary. By clicking on the UKIRT DB link, you get a search reporting back UKIRT J band (near infrared) images of the Kepler star from the WFCAM Science Archive. The typical pixel scale is 0.8-0.9 arcseconds per pixel, which allows us to zoom in within a few arcseconds of the Kepler target. (Thanks to Mike Read from the WFCAM Science Archive for helping set this up and to Phil Lucas for generously letting us link to the data in this way).

—-

Other updates to the site include updating the lists of known eclipsing binaries, false positives, and Kepler planet candidates. The Kepler team last week released their list of planet candidates and false positives from analysis and vetting using data from Q1-Q8. The Talk labels have been updated to reflect this. The eclipsing binary list comes from the July 2012, since that’s the last static list to be released.

Planet Hunter Kian awarded the Chambliss Prize

Congratulations to Planet Hunter Kian Jek, who just received the Chambliss Amateur Achievement Award! This is the premiere award for amateur astronomers presented by the American Astronomical Society – and we think it is highly deserved. Many of you know Kian, who works tirelessly on the site and to a large part is responsible for the dramatic success of Planet Hunters. He not only plays a leading role in hunting down planets, but has been responsible as well for much of the work on variable stars that the project has produced. This award is a suitable acknowledgement of his contributions, and we hope it also serves as recognition for all of the Planet Hunters by the American Astronomical Society. When solicited for a comment on the 42 new candidates in the latest Planet Hunters paper, co-author Kian (his third paper!) wrote:

“As someone who grew up with the Apollo moon landings, whose childhood imagination was fired by Kubrick’s 2001 and the original Star Trek, I never had any doubt that planets around other stars existed and that one day we would discover them. But I never dreamed that we would find them in my lifetime, let alone being involved in their discovery. Although there are over 700 discovered since 1996, each new planet opens another door to a strange alien world, some of them we could not even imagine could exist. Planethunters is an exciting project that allows citizens and scientists participate in pushing the final frontier ever slightly further.”

Frequently Asked Questions

We’ve had many new people join Planet Hunters over the past several months (Welcome to all of you), and I thought it would be good to spend a blog post answering some of the recurring questions that get asked on the forums that our Talk moderators, the science team, and other members of the Planet Hunters community have answered in one spot for both new and veteran volunteers.

Q: How many people look at each light curve?

A: Currently 5 people review the same 30-day light curve. We combine the results from all the classifications of that light curve to make an assessment to decide if there is a transit or not. This is known as the wisdom of the crowd. By combining the results of many non-experts you can match or outperform an expert classification. You can read more about how we do that for Planet Hunters here. Once there are 5 classifications the light curve it is retired and a new unclassified light curve makes the list. We do have some preferences for what light curves get shown, but it’s roughly a random draw with a few rules. Those rules prioritize the light curves so that for example we show new light curves that don’t have known planets more than showing Kepler favorites or known eclipsing binaries to optimize changes of discovering something new.

Q: Is it possible go back and reclassify a light curve I’ve already classified?

A: No, once the classification has been submitted you can’t go back and change it. It’s okay if you’ve missed something or made a mistake. Usually if you see something other people who classified a light curve will as well and will have marked it.

Q: I just started with Planet Hunters. Am I starting from the beginning and seeing old data that’s already been classified by previous classifiers months ago?

A: You’re seeing the newest data we have on the website. Though we are currently showing data that has already been searched for planet transits by the Kepler team’s automated routines, we think there may be transits that the computer algorithms may have missed. Starting in 2013, the Kepler light curves will be released publicly at the same time as the Kepler team gets to see it, and we’ll be uploading that data as fast as we can go through classifying Quarters on the Planet Hunters website.

Q. What’s a Kepler favorite, and why doesn’t it show up under My Candidates?

A. A Kepler favorite is a star the Kepler team thinks has planets of its own and have identified what they believe to be planet transits. We don’t list those on your planet candidates list. We only list things Planet Hunters has identified as new planet candidates.

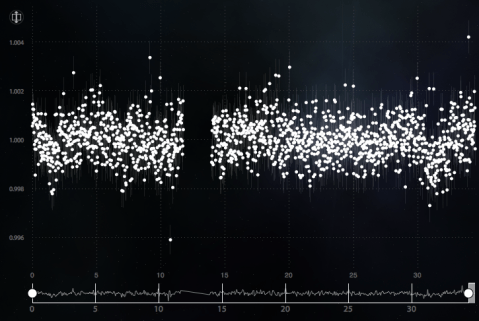

Q. What’s an eclipsing binary (or what’s an EB)?

A. An eclipsing binary or EB is a pair of stars that are gravitationally bound to each other and orbiting their common center of mass,. We call this an eclipsing binary because the smaller star passes behind and in front of the larger star along our line of sight. When the smaller and cooler of the two stars transits in front of the larger hotter star you get a drop in light like with a planet . We call this drop in light a primary eclipse. The difference from a transiting planet is that a planet has no significant light in the optical compared to a star, so when it passes behind you typically don’t see anything observable in the optical. In this case we have two stars that are luminous so we loose the light of the second star when it passes behind the larger star. That produces a smaller drop in light we call a secondary eclipse. So for a eclipsing binary light curve you get a big dip small dip repeating pattern. The light curve looks something like this if the stars are well separated:

You can learn more about eclipsing binaries in these blog posts (here and here)

Q. I can only mark 18 transits before the Finish button goes away. What do I do?

A. This is a known bug in the interface. We won’t be fixing that in this version of the site. Just mark as many as you can before the Finish button goes away (that should be about 18).

Q. How do you want me to mark EBs in the classification interface?

A. Mark the primary and secondary eclipses or as many as you can before the submit button goes away. The science team will sort out if those are planet transits or stellar eclipses in the light curve.

Q. What if I discovered a planet, will you let me know?

A. Yes, if you were the first to identify a candidate that we can confirm is a planet or the science team writes a paper where the majority of it is devoted to a specific candidate we will ask you to be a co-author on the paper. The Zooniverse has your contact info from when you signed-up. So not to worry we’ll email you. Also since we can’t stick 200,000 co-authors on a paper, every we paper write references our authors page to acknowledge the contributions from all our volunteers who make the science possible.

Q. What are those gaps in the light curve? Is that a big planet transiting?

A. If you see gaps like the ones shown above, that’s not from a really big planet or star that blocks out all of the light from the Kepler target star. It just means that Kepler isn’t collecting data. Usually that’s because Kepler is pointed away from the Kepler field so it can aim it’s antenna towards Earth to send its observations back to NASA. The other reason there might not be data is because something has happen on Kepler and it has entered safe mode to protect itself. When that happens the spacecraft isn’t taking data.

Q. What is the difference between SPH number and APH number?

A. Kepler is monitoring about 160,000 stars. We have chosen to show sections of the light curve that are the same size as the first quarter (35 days), and therefore Quarter 2+ light curves are broken into three sections of roughly 30 days (each quarter is typically 90 days except for Quarter 1). We have 5 days worth of overlap in each section, so that we don’t miss any transits that happen at the starts and ends of where we separated the light curves. You can tell which part of the light curve you are looking at by the APH#. The first two numbers are quarter and section. For example, APH22332480 is section 2 of Quarter 2. Quarter 1 light curves start with APH10. We use APH for the light curve sections and SPH for referring to the star itself. For the SPH numbers the first two numbers refer to what quarter the star first appeared in the public data set. For example, SPH21332480 first appeared is Quarter 2 Section 1. The star source pages (like http://www.planethunters.org/sources/SPH10129795) contain all the sections of light curve (we have available on the site) for you to review and the x-axis is the days from the first observation, so you can look for repeat transits in other sections of the light curve easily. Also available on the source page is a downloadable CSV file which contains all the available light curve data we have on the site.

If you have other questions, check out our FAQ site or Site Guide. If you don’t see the answer you’re looking for, do ask your question on our Talk website

Happy Holidays

Image Credit: Steve Harris (swh) from Flickr http://www.flickr.com/photos/steveharris/5255090489/

Happy Holidays and Merry Northern Winter (and Southern Summer) Solstice from everyone on the Planets Hunters team.

In spirit of the holiday season, each day this month, the Zooniverse has revealed a new gift on the Zooniverse Advent Calendar. Two years ago, Planet Hunters was hiding behind one of the doors. This year there were several Planet Hunters themed surprises (including the background for the Advent Calendar which might look very familiar) :

In case you missed them:

Day 1: Zooniverse Publications Page – Including 3 Journal published/accepted Planet Hunters papers

Day 12: A Live Chat with members of the Science Team

Day 16: Planet Hunters Anniversary Poster composed of all of our volunteers names (can you find yours?)

And be sure to check out tomorrow as the last door opens on the Advent Calendar.

Wishing you a very Happy Holiday,Merry Solstice, and Happy New Year from us to you.

New Publications Page

With the start of December, it’s that time of year again. The Zooniverse Advent Calendar is back. Each day this month, a door opens and there’s a new surprise. Planet Hunters was behind one of those doors two years ago. On Day 1, the door revealed the new Zooniverse publications page. There you will find all of the peer-reviewed and Journal accepted papers for Planet Hunters as well as the other projects that make up the Zooniverse. It’s been a busy year with our first paper which was accepted for publication in 2011 officially printed in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 2012, 2 more papers accepted (Schwamb et al. 2012 accepted and published in Astrophysical Journal; Lintott et al 2012 accepted to Astronomical Journal), and the PH1 paper submitted. You’ll see the PH1 paper isn’t listed there yet. That’s because it’s still in the peer-review process. We’re the midst of responding to the referee’s report and resubmitting the paper to the Journal and the referee. We hope to have it accepted and listed there on the Publications page soon.

P.S. Thanks for all of your hard work to help make these publications happen. We can’t add thousands of names to the paper authorship, but we acknowledge your time, effort, and contribution to all of our publications on our authors page .We update the authors page each time a paper is accepted for publication. The link to the authors page is in the acknowledgements of every Planet Hunters paper.

P.P.S. The background image for the Zooniverse Advent Calendar might look very familiar.

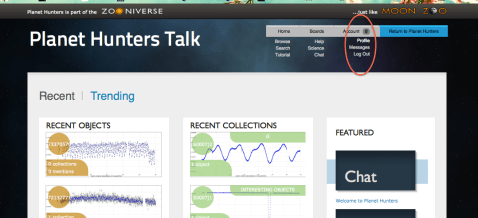

Some New Features in Planet Hunters Talk

We’ve added some new features to Planet Hunters Talk in the early Fall that you might not be aware of. For our new volunteers, Talk is our forum/discussion tool where you can share your thoughts about light curves you’ve classified and interact with other members of the Planet Hunters community.

If you haven’t been to Talk before you can get to the site in two ways – one by directly going to http://talk.planethunters.org/ or when you’re classifying a lightcurve and answer “yes” to “Would you like to discuss this star?”. When you answer “yes”, you are brought to the dedicated page for that specific light curve you classified on Talk where you can write a 140 character comment, add a twitter-like hashtag, or start a side discussion. Talk also allows you to collect similar light curves together in collections.If you’re new to Talk or just want a refresher, we’ve added a brief tutorial which you can find here.

I wanted to share some of the new features that have been added a few months ago that you might not be taking advantage of. One of our new features is emoticons 🙂 . The other is “Watched Discussions.” For any discussion on talk you want to stay up to date on, you can now receive emails when there is a new response posted including the text from the posted message.

For all discussions on Talk below the title you’ll see a link labeled “watch discussion.” By clicking that link the thread will be automatically added to your account’s “watched discussion” list, and you will immediately start receiving emails when there is a new post. This feature exists both for the message boards and for side discussions about specific light curves/stars.

You can find out what discussions you are watching and will receive emails for by going to your profile page. From there you can also change your preferences and remove or modify the list. If you move your mouse over the Account button on the top right of the Talk website, you’ll get a menu that includes the link to your account profile. Click on “Profile’ and from there you can change your preferences and the discussions you are following

Once you’re on your profile page – you’ll see options to enable/disable receiving email as well as the ability to remove Talk threads from your Watched Discussions” list.