Heading to the 2nd Kepler Science Conference in November

The 2nd Kepler Science Conference is 7 weeks away on November 4-8th. From the science team, Ji, Tabetha, and I will be heading to California to attend. The conference will be hosted at NASA Ames where the Science Operations Center for Kepler is based. The first Kepler Science Conference was held there 2 years. You can read more about the workshop from the accounts of Planet Hunters volunteers Kian, Daryll, and Tom who also attended.

At the time of the first Kepler Science Conference, Planet Hunters was just a few weeks shy of its first birthday, and it was the 2nd scientific meeting that I had presented any Planet Hunters results at. A lot has changed since then; Kepler has aided in ground-breaking discoveries, and our view of planet formation and the architecture of planetary systems has dramatically changed with the analysis of Kepler data. Also in those past 2 years, much science has come out of Planet Hunters (thanks to your clicks) including PH1 b and PH2 b and many other planet candidates. You can see all the submitted and published Planet Hunters papers here.

I’ve submitted a talk abstract to present the Planet Hunters TCE review in November. I know, Tabetha has also submitted a Planet Hunters poster abstract about the “Guest Scientist” program for the conference as well. We’ll know at the end of the month if the abstracts were accepted.

At Protostars & Planets VI, I presented a poster on my preliminary work on the TCE review. In between moving to Taipei, Taiwan in August and settling in (I’m now a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics at Academia Sinica [ASIAA]), I’ve been working on continuing that analysis and starting to interpret the results. I find conferences good motivators to make progress on my research projects. I always want to have something new and different to say from the last time people saw me present. So, this month is all about working on the TCE analysis for me. With your classifications from the TCE review, I’ve been able to make a list of all the transit-shaped TCEs and with some preliminary criteria made a rough planet candidate list that I presented in July. I’ve been now looking more at the additional cuts I had made to go from that transit-shaped list to list of planet candidates. I think at this stage, I’m happy with the reasoning for the specific cuts based on other properties of the TCEs to remove false positives. Now, it’s looking at how to estimate an efficiency and see what things we might be missing in our list. In addition the Kepler team has finished vetting the list of new Kepler Objects of Interest (KOIs) from Q1-Q12 into planet candidates. I am now starting to look at what are the differences between our Planet Hunters-derived list and the current cumulative Kepler planet candidate list. In particular what things did we include that they didn’t (and vice versa) and how that relates to transit depth/size of the planet.

The Beginning is the End is the Beginning

There has been much talk about Kepler’s reaction wheels over the past year, when in July 2012 one of Kepler’s four spinning reaction wheels (wheel 2) failed. Kepler uses these wheels to precisely point the spacecraft so that the stars it is monitoring stay nearly at the same positions on Kepler’s imaging plane in order to achieve the ~30 ppm photometric precision required to detect Earth-sized planets transiting Sun-like stars. Kepler’s thrusters used for coarse adjustments are unable to provide that kind of sensitive nudging.

Kepler only needs 3 reaction wheels to successfully keep pointing for the exoplanet observations, so with 1 out of 4 wheels non-functional, observations could continue. It was known at that point that another reaction wheel (wheel 4) was already acting up in similar ways to the failed wheel 2. It was unknown at that point how long the wheel would last. It could be days or months or years, and NASA was investigating ways and implementing strategies in attempts to prolong the lifetime of Kepler’s remaining working reaction wheels.

In May of this year, after 4 years of light curves, Wheel 4 failed halting the exoplanet observations in the beginning of Quarter 17. (Read Chris’ take on Wheel 4’s failure). Kepler was placed in a configuration to preserve fuel while NASA explored ways of reviving one of the 2 broken wheels. After engineering tests, NASA announced two weeks ago that the failed reaction wheels are unrecoverable. The spacecraft is in an Earth-trailing orbit, not reachable for an astronaut servicing mission. This means the end of Kepler’s exoplanet transit observations, and NASA is exploring alternative observations that Kepler could be used for (like looking for Near Earth Asteroids).

This is the end of the Kepler’s exoplanet transit observations, but this in many ways just the beginning of the mission’s next phase as the focus shifts solely to analysis of the data that has been collected and thinking of new ways of processing the existing observations to find smaller and smaller planets. The mission is far from over. Although there will be no more light curves coming from Kepler, there are still many discoveries yet to be made and science to do. There are still ~ 2 years of worth of Kepler observations already on the ground that the Kepler team and the astronomical community have yet to fully analyze. To fully search and analyze all the Kepler data will take at least another several years, keeping astronomers and citizen scientists busy until the launch of TESS. Kepler has revolutionized the field of exoplanets and will continue to do so for a long time to come.

What does the news about Kepler mean specifically for Planet Hunters? At Planet Hunters, we have only searched a small fraction of the Kepler quarters. In addition new and better data reduction techniques have been implemented by the Kepler team to improve the quality of the Kepler light curves and help reveal planets that may been invisible previously. We plan to search all four years of the newly reprocessed light curves with Planet Hunters. We need your help more than ever. We’ll be serving light curves (with previously unknown planet transits likely lurking in the dataset) needing classifications for a long time to come!

So join us today, as one phase of the Kepler era ends and the next one begins. Help continue the exoplanet search today at http://www.planethunters.org

More from Protostars and Planets

Last month, many of the Planet Hunters science team attended the Protostars & Planets VI conference in Heidelberg, Germany. The conference happens every few years and serves to summarize the state of the field from stars to exoplanets and everything in between. I presented a poster on the preliminary results from our TCE review and Yale graduate student Joey Schmitt presented a poster on the current status of the Planet Hunters planet candidate effort . Most of the posters from the conference have been posted online. You can find my poster here and Joey’s poster here. The talks from the conference are also online (including a talk on Exoplanet Detection by Planet Hunters PI Debra Fischer).

Protostars & Planets

Greetings from Heidelberg, Germany. I’m here with most of the Planet Hunters science team for the Protostars and Planets VI conference. Astronomers, planetary scientists, and cosmochemists from across the world have gathered for this week long conference to discuss the state of the fields in star formation, young stars, circumstellar protoplanetary disks, planet formation, and exoplanets. The last conference was in 2005 (before I started graduate school) so there is much to talk about in terms of how what we know about star and planet formation has changed.

There are about ~900 people attending the conference. Unlike most conferences, Protostars & Planets has one session per day, with several half-hour talks based on the chapters being written for the conference proceedings. Planet Hunters PI Debra Fischer is giving the summary talk on the discovery of new exoplanet systems. Joey Schmitt, a 2nd year graduate student at Yale, and myself will be presenting posters on Planet Hunters results. Joey is presenting a poster titled “Planet Hunters Update:Many New Planet Candidates Identified by Citizen Scientists from Kepler Data, Including Several in the Habitable Zone”. Joey’s poster is a summary of the candidates from Ji’s paper and some new PH planet candidates he has been working on characterizing. My poster is on the first results from our TCE review highlighting that we have a list of all transit-shaped TCEs.

Zooniverse Live Chat

A small team of scientists and developers from across the Zooniverse are gathered at Adler Planetarium in Chicago this week to pitch and work on ideas for advanced tools for some of your favorite Zooniverse projects. Our goal is to come up with some tools and experiences that will help the Zooniverse volunteers further explore, beyond the scope of the main classification interfaces, the rich datasets behind the projects in new and different ways. As part of the three days of hacking, there will be a live chat with representatives from Galaxy Zoo, Planet Hunters, Snapshot Serengeti, and Planet Four (as well as a special guest or two) tomorrow Thursday July 11th at 2pm CDT ( 3 pm EDT, 8 pm BST). We’ll also give you an inside peek into the US Zooniverse Headquarters on the floor of the Adler Planetarium where much of the coding and…

View original post 51 more words

ZooCon 13

Today we have a guest post from Jo Echo Syan (echo-lily-mai) , one of our dedicated Talk moderators, who attended ZooCon13 in Oxford, UK last month. Jo has been a member of the Zooniverse since 2009 and is also a Merger Zoo moderator over on the Galaxy Zoo forum. Completing a 1st class degree in fine art is currently exploring how art and science can fuse together with Enjoy Chaos

Chris Lintott one of the founders of the Zooniverse and representative of Planet Hunters at ZooCon13 has kindly offered to fill in the gaps and answer my questions that were left unanswered in a ball of scribbled notes…

Q: Is it correct that PH has achieved 5 peer review papers and how does that compare with the other Zooniverse projects?

A: We’re on four, and a fifth (Wang et al) waiting some observations to deal with a technical point the referee raised. That puts Planet Hunters joint second amongst Zooniverse projects, but I reckon we have lots more papers to come as more people begin to use the data.

Q: Can PH continue without Kepler? I know you go on to talk about this later, so in one word yes or no.

A: Yes.

Q: The team had been warned at the beginning, that people don’t look at graphs for fun!! PH groups were wanting to look at results. Does this make Planet Hunters any different to other Zooniverse project users?

A: Now that’s a good question – we don’t really know, although we’re taking a look at how people behave. One thing the planet hunters are is dedicated; they stick at the task more than most other Zooniverse projects – probably because they really want to find a planet!

Q: 1995 first planet discovered, by 2013 there is now believed to be 17 billion earth like planets in the Milky Way.Are these amazing figures correct? What other amazing leaps do you think will be made within a similar time frame?

A: There’s an error-bar – and you can argue about what Earth-like means – but that sounds about right. With results from Kepler and elsewhere we really have learnt that planets are a very common feature of the Milky Way, and it’s possibel that more stars have planets than don’t. This makes exoplanet hunting one of the most exciting things happening anywhere in science right now, and I don’t think the pace is about to let up. As we find more planets, the focus will shift to trying to characterize those planets, maybe even detecting their atmospheres, and for that we need to look for planets around brighter stars than those that Kepler studies.

Q: What is Earth-like eg. Rocky, good temp, and water making it habitable. How many rocky planets are there that are close to parent stars? Do you think looking at the facts and figures that it is common for habitable planets to be found in most/all solar systems?

A: We don’t know yet. It’s likely that the dataset that Kepler left us has enough information to answer this question, and that’s why it’s important that Planet Hunters (and all the other groups looking for worlds of their own) keep sifting through the data.

Q: How did planets form? What are disks around stars and how did they form?

A: When a star forms from a collapsing cloud of gas and dust, leftover material forms a disk around the star, and it’s from this disk that the planets form. Here’s just such a disk around the star Formalhaut, made visible by blocking out the light from its parent star

The point I was trying to make was that one of the things that our amazing stock of planets lets us do is just our understanding of quite how this process works.

Q: Kepler stared at 160,000 stars. It seems to find lots of super earths (we had a joke about it sounding better than slightly bigger than earth planets) Neptune sizes are the most common, but we are getting more earth and super earths being discovered. How will we turn these candidates into confirmed planets? What needs to happen in the future?

A: Most of them probably will never become confirmed planets. Doing follow-up on stars as faint as those in the Kepler field needs a large telescope, and we typically use the Keck which is one of the largest in the world. If we wanted to systematically confirm all the Kepler candidates we’d have to kick every other astronomer off the telescope, and even then it would take years. Luckily, we don’t have to do that – if all we’re interested in is the statistics of the planet population, we just need to observe enough to understand what the error rate is, and then we can do our science that way. If you know that 95% of your Earth-sized candidates are real, for many purposes (not including space travel) it actually doesn’t matter which ones they are.

Q: There was a two star system found, the Keck telescope was used to check it really was a planet and not just a candidate and it turned out to be a four star system!! PH1 b Is that correct? Why did it need to Keck to see that it was a four star system, why could it not be seen in the light curves?

A: We picked up the signal of the third and fourth stars by using Keck to make what are called radial velocity measurements, looking at the wobble of the stars back and forth as they orbit each other and the planet orbits them. We saw extra movements which we traced to the extra stars – I don’t think those two stars eclipse the others from our perspective in Earth and so they wouldn’t have been picked up by transits.

Q: There is an instability region where planets can simply not exist but all the planets found live on the edge of this region. Does our planetary system exist on an edge of an instability region?

A: This was actually a comment about planets around binary stars, like PH1. It’s intriguing to me at least that wherever we’ve found these worlds, we’ve found them almost as close to their parent stars as they can be without being on an unstable orbit. That must be telling us something about their formation.

Q: 42 planet candidates missed by Kepler etc. found in habitable zone were found by Planet Hunters at the Zooniverse!!! Probably ~37 or so will turn out to be real. We are waiting for PH2B. Why did Kepler miss these candidates?

A: Because it’s hard to get everything! An automatic system doesn’t catch everything we do, although as with previous Planet Hunters discoveries I expect that the automatic routines will learn from their mistakes now we’ve pointed them out and get steadily better and finding these things.

Q: And there was a brief discussion for future developments in the naming of planets.Do you think planets will eventually take more familiar names in the future as people become more aware of other planetary systems?

A: A decision was made a few years ago not to give official names to exoplanets – and it’s not a decision I agree with. I also think it’s pretty clear that the system is broken (it seems weird to me I can call a planet Planet Hunters 1b or Kepler 22 but not Arcardia or Lintott or other such names). The International Astronomical Union, who make decisions about such things, look like they might be moving position so I’m hopeful that we’ll get to name planets properly one day.

Q: Kepler is not well. What is wrong with Kepler?

A: It’s having trouble pointing in the right direction due to problems with its reaction wheels – there are still a few things left to try, but it looks like its main mission is over.

Q: It’s still looking for a planet with a one-year approx. orbit earth sized planet.Has a planet with a one-year approx. orbit not been discovered yet?

A: Several – including lots of the Planet Hunters candidates. We’re still looking for the really small ones, though – and they’re probably hidden in the data.

Q: PH site is still active and has data to look through I guess enough said!! What else is in the data? Stars they are all different to our sun. Why are there not more stars that are the same?

A: It seems that stellar variability is important – as people will know from the Planet Hunters light curves, stars brighten and fade all the time, and Kepler has helped us understand how different each and every star is. There’s loads of work here just on stellar astrophysics alone.

Q: Why are heartbeat binaries so interesting?

A: They’re just unexpected and cool. But also the rapid changes in brightness might allow us to work out what’s going on inside the stars, just as geologists use seismograph data to model the inside of the Earth.

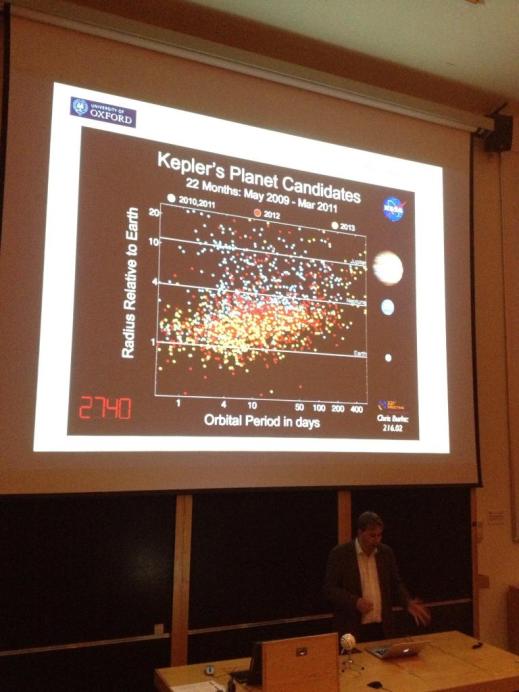

Why is there a gap on the bottom right of this image?Why are PH collaborators so good at filling in the gap?

A: Small planets are harder to find and it takes longer to transit if you’re further away from the star. This gap may be real, but first we need to work out what could be lurking there that we haven’t found yet.

Q. 2 stars going round each other can causing tides, oscillations like in the heartbeat stars, and with asteroseismology we can study the interior of stars. Has the Zooniverse got any future projects planned to study this?

A: Watch this space!

Q: PHer’s have a lot more to do. The TCE review had a catalogue full of candidates. These are folded light curves, which I believe this survey is now complete!?

A: Yep, and Meg’s working on the results!

Q: Do we know how accurate the Kepler algorithm is?

A: We can test it – Schwamb et al. was the first attempt to use Planet Hunters to see how they’re doing. The answer, it seems, is ‘pretty well, but not perfectly’.

Q: The TESS telescope will look at brighter stars. Live data and take us beyond the end of the decade. Will working with TESS data appear the same as the light curves that we are already used to classifying?

A: TESS will target brighter stars so we might see a lot more detail on the light curve, we haven’t really had a chance to think about it yet.

Q: Are tools being built for all different Zooniverse projects?

A: I’m sitting in the Adler in Chicago about to have a meeting about this – we can’t promise tools for all projects, but Planet Hunters will definitely be included. Advanced tools are currently being built and we should watch out for them at the end of September. We should thank people on the PH Talk site who have patiently spent their time trying to help others and explaining by writing’how to’ pages. The Zooniverse team wants to help all people use these types of tools and have easy access to them.

Tales from Waimea Part 4 – Observing Report

This is the second half of part 4 of my Keck NIRC2 observing log. (See Part 1 and Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4a).

The night you’re scheduled is the night you have, and you only worry about what the weather and conditions are when your data is being taken. Sometimes you get the only good night in the entire month of other observing runs and sometimes you get the day it rains. You might have awesome weather and your instrument malfunctions costing you hours as the operator and support scientist try to troubleshoot it. That’s the gamble with observing and part of the reason I love it. I’ve spent my share of time staring at humidity sensors trying to will them down to the threshold for the dome opening with no avail. You have to deal with what the night throws at you whether it’s bad weather, amazing conditions, or instrument malfunctions. If I don’t get the conditions I want, it’s tough luck for the observer. That’s it for the semester, and you’ll need to try again and apply during the next the call for proposals. That’s the gamble of an observing run.

So I started the night doing really bright targets and sorting instrument commands and forgetting and remembering to open the camera shutter and the appropriate dither command and offset to use as I got situated because the Kepler field wasn’t high enough in sky . When I got on to the Kepler field, I took the first test image to sort how long the integration should be . I’m in the linear regime (which means what it sounds like. It’s the range on the detector where a photon hitting generates X electrons on the camera CCD. If I have too many counts already on the detector, then this can cause the CCD to switch regimes where it doesn’t generate X electrons any more per photon and that means you don’t know how many photons from the star you actually received) so if I want double the counts I double the exposure time. I do that and I saturate the detector (where there are too many electrons due to photons hitting a given pixel on the CCD that they spill over onto surrounding pixels). Um…. then I go back to 4 times less and I get the peak counts I got with my first exposure (which was twice as long! What gives?). I call over Marc my support astronomer because something’s up. (he was awesome and really helped me to get familiar with the instrument and get feedback on what the AO system was doing given the conditions. Thanks Marc!) o Either I’m doing something wrong or something’s up. We go through the same logic. Okay let’s double the exposure. Now we get the same peak counts as were on the previous exposure that was half as long. What’s going on?

It was perfectly clear at the summit above Keck last night, but the turbulence in the atmosphere made it a constant struggle last night. The adaptive optics system corrects for the effects of the atmosphere and reduce the smearing of the star on the CCD detector, but if you’re seeing (how big the stars appear in your images due to the atmosphere smearing) is changing faster than the AO system can keep up and by a wide range the AO struggles to keep up. That’s because the wavefront sensors measuring how the light is hitting the telescope and direct the mirrors to deform to compensate, but that correction is no longer correct and the seeing is now something different, so you’re get a lag. I still get correction but it means that the counts in the pixel wells of the CCD that the camera actually measures are changing rapidly as the size of the star is oscillating back and forth. Not good news.

Here’s the seeing monitor from Mauna Kea for last night. You can see it was just rapidly oscillating and going towards big values. Average seeing on Mauna Kea in optical is ~0.8 arcseconds.

Red and blue points are from different elevations and you can see how widespread the points are in a short period of time. The absolute value isn’t necessarily what we measure on the telescopes, but we see the same relative changes

I’m the observer it’s my call what to do. So as Marc is explaining this could be kinda AO lag and the fact the seeing is just rapdily changing. I look at my target list notes and see that this Kepler star is at the mid range of the Kepler Input Catalog magnitude range. It’s 13th magnitude (it was high priority) but I have a few brighter stars that are 10th magnitude (in astronomy lower magnitude equals brighter star). The AO system is using the target to do the corrections, so if it’s not getting enough photons to adjust quickly then maybe going to a brighter star will help. So after a bit of playing around with different setups, I make the call to move to a 10th magnitude star on my list.

The same thing is happening but we’re getting better counts and the AO system seems to behaving a bit better. So that’s it. My observing plan is out the window. I decide targets aren’t going to get observed by priority but in order of magnitude working my way from brightest to fainter going from 10th, than 11th to 12th, and knowing I’m probably going to skip all the 13th and 14th magnitude stars. I had been mulling getting two colors (J and Ks) for each target before the start of the night. I ultimately decide to only get Ks, and J will only be if I see a faint companion in the image. The conditions could get better, and then I’d be in business. If they do, I’ll move on to brighter targets and adjust the where I’m moving Keck to next, and the seeing did improve in value (it was still varying by the same amount) so I could get 11th and 12 magnitude stars later on before it went back to being bad right before the Kepler field set.

I can take lots of short exposures but taking lots of short exposures and reading them out has a big overhead or I can take a bunch of short exposures and coadd them together in a single read out. I go for the latter after consulting Marc. I decided that saturation is at around 10000 counts, if I can keep the counts around 2000 even if the seeing is causing flucuations by a factor of 2-3 I’m still well in the linear regime and can use the observation. I am gambling a bit in that if one of the exposures that get added to together to make the coadd is saturated I’ve ruined that entire image, but I can check to make sure the counts are what I expect for the target peak counts I’m aiming for.

I also decide to do overkill on these targets. Do 3 times as may exposures+coadds at each part of the 3 point dither and pound on the targets (sometimes repeating the dither pattern again) to try and get useful photons. This is because if there is no contaminating faint star visible, we want an estimate of how bright of a companion we could see. I’m already getting lower counts than expected and the seeing is smearing the stars out over more pixels with additional readnoise and sky background, so that decreases my sensitivtiy. I don’t want to find out that all my observations were useless because they didn’t go deep enough to detect any possible stellar contaminators around these stars.

At this point, all I can do is crank the music up, drink more caffeine, and fight on through the rest of the night. Every target I spend several minutes taking test exposures getting a feel for the fluctuation in counts, and trying to get the peak counts in my goal ~2000-3000 counts and make sure that that exposure doesn’t seem to be giving me the danger non-linear regime counts. Then take the coadded exposure, see what the counts are and does the average peak counts divided by the number of coadded exposures give me back around ~2000-3000 counts, if not I need to readjust. I also look at the shape of the star (or the point spread function PSF), if one of the images saturated it should start looking funky).

I can’t help going back and trying to think about where I wasted time, what I should do differently for the next time on NIRC2 and how to be better for the next observing run. Ultimately I made a decision, on what to do for the observing scheme. Some of that came from gut feeling from my past experience observing. Things I’ve learned from watching more senior observers who trained me when bad nights happened, when things went wrong, and asking questions during the observing run.

But did I make the right call? Did that give me anything useful? I think there are moments I won the battle (but not the war) and the counts are linear but only fully reducing the data will tell. I’m planning on trying to do it myself, so that will take some time. I know there’s at least one source with a neighboring star that’s roughly 10% fainter than the Kepler star that I could see at one point in the night, and I managed to keep two filter band observations, to get the color so we can estimate the contaminator’s brightness in the Kepler magnitude. So I’m hoping those observations will be useful.

It’s one of those frustrating nights where all you can do is keep collecting photons, and try to deal with Mother Nature the best you can. A big thank you to my operator Joel, who was super knowledgable, happily answered questions, and really helped make things go smooth once I was on my own despite the variable weather conditions.

Ultimately, we’ll have to wait and see what the reduced data looks like.

PS. Chris posted my tour of Keck Remote Ops II yesterday, if you want to see what it’s like in Keck HQ.

Tales From Waimea Part 4- Sunset approaches

It’s a few minutes before sunset. I’ve gotten the “keys” to Keck 2, and I am currently making the final preparations for the start of the night. It looks like it’s going to be a clear night from the weather report, and the cloud deck has already sunk below the summit. The instrument, NIRC2, has been checked out and initialized. Calibrations including dark images and flat field images have been taken. My starlists are uploaded. I’ve got plots of where the targets are in elevation (or airmass) on the sky. As you can see from the plot above, I’ll be mainly looking at things all in the same place. Not a surprise since I’m going to be looking at the stars in the Kepler field which span ~100 square degree patch of sky. The beginning of the night, the Kepler field isn’t quite up, so I’ll be doing other targets for collaborator, but once the Kepler field is high enough, we’ll slew Keck 2 there and get to work.

Since it’s my first time on the instrument, the support astronomer will stay with me for the first part of the night, and leave once I’m settled in. I won’t control the telescope, the operator on the summit will do that, but I’ll have control of the camera and decide which targets we go to next. You can check out the all-sky-cam for Mauna Kea and see how it looks during the night here.

Tales from Waimea Part 3

This is part 3 of my Keck NIRC2 observing log. (See Part 1 and Part 2).

So I can’t sleep, so I decided to go take some photos of where I’ll be sitting all night. So here’s what it’s like to be in Keck Remote Operations Room 2.

Telescope status info on the big screen. Smaller screens below will have all the instrument information and control interfaces. I’ll be sitting here for the night.

- Welcome to the heart of remote ops 2

Polycom that allows me to remotely video conference with the telescope operator on the summit (I’ll at sea level in Waimea not on the summit). You can see a bit of a view into the summit control room.

Tales from Waimea Part 2

Greetings from Hawaii. I’m here for observing on the Keck telescopes. It’s 5:45am in Hawaii, and the Sun has just risen. I’m sitting here in my Keck Visiting Scientist Quarters (VSQ) dorm eating a microwaved breakfast burrito and just about to head to bed. My observing night is today or rather tonight on June 28th local time in Hawaii, but I’ve been up all night to try and adjust to being on a night schedule so I’ll feel better tomorrow when I actually need to working . I also go to spend the later part of the night sitting in while last night’s observers were taking data. I’ll get to that in a bit, but I want to talk about earlier in the day first.

Yesterday afternoon and evening, I tasked myself with reading over the instrument manuals and webpages again, taking notes, and typing up a cheat sheet of useful commands, instrument parameters, and things to remember. This included a walk from Keck to a taco joint a short distance down the road where fish tacos were hand and instrument manuals were read.

I took some pictures on the walk over on my quest for tacos to show you the main Keck HQ building from the street side. You can see in the image, the glass window has hexagonal panes. That’s a nod to the Keck mirror design which is an assemblage of 36 hexagonal mirrors combined to make the full 10-m collecting area.

The early evening, I slept so I could be up and awake much later in the evening to sit in and eavesdrop on the current night’s observers who had the second half the night. I arrived around 2am, and they graciously let me hang out in the remote room typing up my notes, and asking questions here and there about using NIRC2 and the natural guide star adaptive optics system. I got a chance to quietly watch over their shoulders to get a sense of what the general procedure was for executing an observation from start to finish. I’m now feeling more comfortable with the NIRC2 guis and command interface for tonight’s observing.

This morning, the skies around Mauna Kea are clear, and you can actually see there’s a mountain in the distance. With my back to the dorms facing the main Keck HQ building, here’s the view of Mauna Kea at early sunrise. If you squint (or zoom in with your camera), you might just make out that there are telescopes on top.

And so with that, I have a starlist to make tomorrow afternoon, and I meet with the support astronomer in the mid afternoon to go over setup and get me situated with the calibration images. I’ll take lots of pictures of the remote room tomorrow, but for now it’s time to sleep.

\

\